-

1 Introduction

Literature in judicial education has paid increasing attention to the question of diversity in the bench as a crucial point to buttress the legitimacy of courts in plural, democratic societies.1x E.C. Alves, ‘Judicial Schools’. Journal of the National School of Magistracy, v.01, n. 2, at 19 (2006). Justice Eliana Calmon Alves is the first woman appointed to the Superior Court of Justice, where she held the position of Minister from 1999 to 2013. Online at: https://bdjur.stj.jus.br/jspui/handle/2011/1991.

In Brazil, this quest for diversity features as a key trait of the broader movement of democratisation of the judicial system that started with the socially progressive 1988 Constitution.2x B.S. Santos. For a Democratic Revolution of Justice (2008). The ‘Citizen’s Constitution’, as it is dubbed, created a number of new institutions (e.g. the Public Defense Office) in an effort to extend effective access to justice to the whole of the population. Moreover, the main commitment it embodies and its solemn declaration that ‘equality and justice are supreme values of a brotherly, pluralist and prejudice-free society’ (Preamble to the 1988 Constitution) implied a requirement that all public institutions – including, of course, judicial institutions – took steps to incorporate these fundamental principles in their managerial organisation and everyday functioning.3x A. Boigeol, ‘The Training of Magistrates: From Practical Learning to Professional Schooling’, Ethics and Political Philosophy Magazine, at 70 (2010).

In regard to the judicial system, this movement towards more inclusive institutions has faced formidable obstacles whose roots arguably lie deep in the social structure of the country. The restricted access to quality education,4x https://www.gov.br/inep/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/censo-escolar/mec-e-inep-divulgam-resultados-do-censo-escolar-2023 (last visited 9 march 2024). which is a privilege of the most well-off,5x M.A. Salvato, P.C.G Ferreira & A.J.M. Duarte, ‘The Impact of Education on Income Distribution’, Economic Studies, v. 40, n. 4, at 795 (2010). Online at: https://www.scielo.br/j/ee/a/LKVPvzm7PdJcbqF7PxY5dsq/?format=pdf&lang=pt. and a longstanding culture of racial6x National Council of Justice (CNJ), Ethnic-Racial Diagnosis of the Judiciary (2023), at 20. and gender bias7x National Council of Justice (CNJ), Report on Female Participation in the Judiciary (2023), at 13. have combined to establish a staggering uniformity in the profile of judges in Brazil.8x National Council of Justice (CNJ), Judiciary in Numbers (2023), at 37.

Evidence of this uniformity is blatant: in a country where 51% of the population identifies as being Afro-Brazilian,9x https://www12.senado.leg.br/institucional/responsabilidade-social/oel/panorama-national/Brazilian-population (last visited 9 March 2024). only 14% of the judges are Black – 9% male and 5% female.10x In Brazil, 46% of the judges are White male, 34% White female and only 14% of are Black African descendants, https://www.cnj.jus.br/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/justica-em-numeros-2023-010923.pdf (last visited 9 March 2024). Although 51% of Brazilians are women, since its creation, in 1891,11x This bias seems to remain dominant in present-day Brazil, unscathed by decades of scholarly and political criticism. President Lula, widely considered as a progressive politician, has appointed two men for the Supreme Court, one of them to replace one of the two women justices in STF. The Court is currently composed of 10 men and 1 woman, all White, https://brazilian.report/liveblog/politics-insider/2023/09/17/brazilians-female-supreme-court-justices/ (last visited 9 March 2024). the STF (Brazilian Supreme Court) has had 169 justices, of which only 3 were women and 3 Afro-Brazilians.12x Brazilian Supreme Court (STF). List of Ministers, https://portal.stf.jus.br/ostf/ministros/ministro.asp?periodo=STF&consulta=ANTIGUIDADE (last visited 9 March 2024).

The results of the Brazilian judicial selection processes have consistently reinforced this bias,13x F.C. Fontainha and P.G. Barros, ‘The Brazilian public tender and the selection process ideology’. Legal Review of the Presidency, at 780 (2015). resulting in a cohort of judges whose educational and social backgrounds are highly homogeneous.14x https://www.cnj.jus.br/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/diagnostico-etnico-racial-do-poder-judiciario.pdf (last visited 9 March 2024). The recognition of this deep bias has led the National Council of Justice (CNJ) to decree, in 2023, measures to enhance the presence of women and Afro-Brazilians in the bench.15x The National Council Regulation 540/2023 provides for gender parity, with an intersectional perspective on race and ethnicity, in administrative and jurisdictional activities within the scope of the judiciary, https://atos.cnj.jus.br/atos/detalhar/5391 (last visited 9 March 2024).

It is in this context that the National School for the Training of Magistrates (ENFAM)16x ‘The establishment of judicial schools in Brazil played a pivotal role in equipping judges to confront contemporary exigencies, facilitating their adaptation to the evolving landscape of legal interpretation and furnishing them with ongoing updates and practical instruction. The enactment of Constitutional Amendment No. 45/2004 served as a landmark, accentuating the significance of judicial academies and mandating the establishment of the National School for the Training of Magistrates (ENFAM).’ E.C. Alves, ‘Judicial Schools’, Journal of the National School of Magistracy, at 19 (2006). requires that all new judges attend intensive initial training to ‘learn how to properly work as a judge’. Given the specificities and peculiarities of operating within each jurisdiction, ENFAM adopts the model for training judges ‘led by peers,’ with focus on legal and career-related topics.17x M.S. Oliveira. M.R.M. Veiga & R.P. Bacellar, ‘Teacher Training in the Scope of ENFAM: Practices, Results and Curricular Perspectives’, Journal of the National School of Magistracy, at 14 (2015), https://www.enfam.jus.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/ArtigoMarizeteBacellarRaiRelatoFofo2015.pdf (last visited 9 March 2024). This option bespeaks ENFAM’s belief that it is judges who should be in charge of the training of other judges. This perspective is anchored in the notion that judges possess a practical understanding of the application of the law, as opposed to the purely theoretical knowledge of professors exclusively focused on teaching and researching law. This traditional model does not encompass teaching from social actors other than members of the law community; nor does it allow for directly experiencing different social realities.

In light of the above-framed context, one of the co-authors of this article was invited by a Judicial School attached to a State Court in Southeast Brazil18x As per the ENFAM regulations (02/2016), the local judicial school is responsible for implementing local training for judges in accordance with ENFAM’s regulations, https://emarf.trf2.jus.br/site/documentos/resolucaoenfam022016.pdf (last visited 9 March 2024). to take part in a group whose mission was to develop an innovative pedagogical experiment for the training of newly appointed judges. The final version of the proposed course abided by ENFAM’s overall directive for peer-based training. Still, it went a step further by introducing an additional instructional component designed to offer the newly appointed judges opportunities to be immersed in the challenging social contexts their judicial activities will impact. This novel component had as its theoretical basis Holston’s and Koppensteiner’s19x N. Koppensteiner, Transrational Methods of Peace Research: The Researcher as (Re)source (2020), at 567. work – both authors whose work was inspired by Paulo Freire’s theory.20x P. Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (2005), at 76.

This article discusses this pioneer experience in a Brazilian judicial school. It presents it as a case study of the possibilities and challenges of having judicial schools as a locus to help judges develop a critical perception of the institutional status quo of courts and its problematic implications and to contribute to enlarging their ability to adopt a more socially responsive approach to their judicial activity. The next section presents the socially homogeneous, elite character of Brazil’s Judiciary. Section 3 describes the structure of a pioneer judicial education course in Brazil. Section 4 brings the views of the participants, and Section 5 sums up the argument. -

2 A Challenging Scenario: Homogeneous Courts of Justice in a Plural Society

As Vilhena Vieira observes in his influential ‘Supremocracy’,21x O.V. Veira, Supremocracy (2008), at 441-63, https://doi.org/10.1590/S1808-24322008000200005 (last visited 9 March 2024). the broad mandate the 1988 Constitution has given courts the power to gradually push the judiciary to the centre stage of Brazil’s political scene. The Supreme Court, in particular, has steadily moved from its traditional judicial restraint to a rather active role in promoting rights and social policies. This movement goes in tandem with the growing prominence of neo-constitutionalism within Brazilian legal circles, which is largely rooted in the intention to bridge the gap between the ‘law in the books’ and the ‘law in action’, thereby contributing to diminishing the stark inequalities that beset Brazilian society.22x Ibid.

Justice Luís Roberto Barroso, the current Chief Justice of the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF), holds that judges, particularly those at high courts, can in their decisions lawfully resort to arguments that extend beyond the strictly legal realm. He holds that these arguments legitimately contribute to the construction of the ratio decidendi. In his words, judges, beyond their purely adjudicative function, should also act as an ‘enlightened vanguard’, whose responsibility is to ‘propel history forward when conservative political forces make it come to a halt’.23x Ibid.

This evolving perspective on the role of the courts, which has gained significant traction across all levels of the Brazilian judiciary, demands that judges, when deciding concrete cases, arbitrate on substantive values and on the desirability of specific social consequences.24x M.R. Veiga, M.S. Oliveira & S. Rauchbach. ‘Teaching Planning in the Context of the Judiciary: Theoretical-Practical Pathways’, Journal of the National School of Magistracy, at 54 (2014), https://www.enfam.jus.br/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Livreto-I-Curso-Planejamento-de-Ensino-Final3jun14.pdf (last visited 9 March 2024); Also, D.E. Cowdrey, ‘Teaching New Judges What It Means to “Be” a Judge’, Internation Organization for Judicial Training, at 54 (2020), https://academic.oup.com/book/32069/chapter-abstract/267878946?redirectedFrom=fulltext (last visited 9 March 2024). Its controversial nature notwithstanding – due to the challenges it represents to traditional interpretations of the separation of powers doctrine – this reading of the function of courts has become both pervasive and increasingly prestigious. This new understanding of the role of the judiciary requires, therefore, that judges take in account, when deciding cases, the likely practical consequences of their ruling.25x Ibid. This theoretically contentious requirement becomes particularly problematic in Brazil. It is not just that judges in the country typically lack the non-legal expertise necessary to make sound assessments of probable consequences of legal decisions – a feature they arguably share with their peers from other jurisdictions. More importantly, it is also that, because they come overwhelmingly from the upper strata of society, they lack direct knowledge of the dire social realities their work is supposed to transform.26x The judicial school where the experience described herein took place conducted an initial diagnosis of the profile of the participating judges in the initial training course. In the sample, 71% (37) of the judges live and/or know only the South Zone and Barra da Tijuca areas scoring the best HDI of the city – home to the upper-middle and upper-class populations. Additionally, almost 80% of the new judges either do not use public transportation or use individual transport such as cars and taxis. According to Holston, in Brazil, it is a recognised fact that an unspoken form of apartheid exists, characterised by various facets of spatial (urban) and institutional segregation. And to go beyond this apartheid requires urban circulation and the meeting of antagonistic patterns of civilities. J. Holston, Insurgent Citizenship: Disjunctions of Democracy and Modernity in Brazil (2013), at 367. The former problem may be mitigated with the help of experts from different areas; the latter, however, cannot be dealt without some degree of direct interaction with the social actors and realities which will likely be directly affected by their decisions.27x Ibid.

Courts are not abstract entities: they are constituted by women and men who decide cases and interpret their judicial roles in light of their individual life journeys, academic backgrounds and professional experiences up to the point of their judicial appointment.Who are the members of the Brazilian judiciary, and from where do these judges originate? Where do they receive their education, and from which social contexts do they emerge? This is a relevant consideration because these judges are entrusted with determining the outcome of individual lawsuits, civil cases and even class actions that possess the potential to halt various public policies. Their decisions profoundly impact society. If judges are recruited immediately upon leaving academia, their exposure to different experiences and social realities is minimal. As such, they may be ill-equipped to address these realities effectively. They enter their roles as judges at a young age, often around 23 to 25 years old, having been immersed in the academic environment. Their socialisation predominantly occurs within the judicial institution, rather than through broader societal experiences, adversities and diversity. They are already going straight to their role as a judge, and this will influence the macro profile of a judiciary. (Speech by the Minister of the Supreme Court, Justice José Antônio Dias Toffoli; translated by the authors)

As Justice Toffoli suggests, homogeneity in the bench is a major hurdle to having a socially aware judiciary. As the CNJ observed, the problem goes far beyond the lack of representativeness of large segments of society in the courts. Extreme social homogeneity also works to enfeeble the legal quality of decisions. Judges are inevitably affected by their worldviews when they interpret facts and law.28x S.B. Blix , Making Independent Decisions Together: Rational Emotions in Legal Adjudication. Symbolic Interaction. (2021), at 23. Though this necessary condition may not be problematic per se – a wealth of legal hermeneutics scholarship centres exactly around the problem of the subjectivity of judges29x Ibid. – it can become so when the worldview in question is embraced by the vast majority of members of the courts.30x K. Luise, S. Gonçalves, T. Wurster & R.B. Ginsburg, Diversity in the Judiciary as a Prerequisite for Legitimacy (2020). When shared by a homogeneous group, this view is prone to be reinforced, leading to a perception that the hegemonic view adopted by the group is the default standpoint, the ‘normal’ – which tends to become normative – perspective from which to understand society, law and the judicial activity. It is based on this shared view that judges will construe legal concepts such as ‘reasonableness’, ‘proportionate means’ and ‘average person’, just to give a few examples.31x D.E. Cowdrey. ‘Teaching New Judges What It Means to “Be” a Judge’, International Organization for Judicial Training, at 54 (2020), https://academic.oup.com/book/32069/chapter-abstract/267878946?redirectedFrom=fulltext (last visited 9 March 2024). These concepts can prove critical to legal decisions, mainly in difficult cases, in which statutes and precedent are blatantly insufficient to adequately dispose of a case. Social diversity and the diverse worldview it fosters are not, therefore, desirable just for the broad social justice goals they may fulfil.32x ‘The absence of diversity within the group of magistrates implies the construction of a standard and universal rationality, formed from similar experiences and disconnected from the plurality and diversity present in society.’ K. Luise, S. Gonçalves, T. Wurster & R.B. Ginsburg, Diversity in the judiciary as a prerequisite for legitimacy (2020), https://www.ajufe.org.br/imprensa/artigos/15413-ruth-bader-ginsburg-e-a-diversidade-na-justica-como-pressuposto-de-legitimidade (last visited 9 March 2024). They are necessary for improving the legal reasoning of courts.33x Ibid. Different interpretations of key concepts such as the ones mentioned above entail that judges articulate better the reasons they have for favouring one interpretation over concurring ones. Diversity thus tends to be conducive to more sophisticated legal reasoning which, it seems fair to hope, should lead to better decisions; better decisions, in turn, help strengthen the legitimacy of Courts.34x Ibid.

The problem pointed out by Justice Toffoli, namely, judges lacking ‘broader societal experiences, adversities, and diversity’ is not, however, addressed by Brazil’s traditional judicial education policies. As mentioned before, according to the National School for the Training of Magistrates (ENFAM), given the specificities and peculiarities of operating within the jurisdiction, the model for training judges is led by peers and focuses on theoretical issues and the internal functioning of courts, rather than on practical experience and social awareness.

Having this context as a background, the article adopts the ethnographic methodology35x J. Clifford, ‘Power in Dialogue in Ethnography’, in G.W. Stocking, Jr. (ed.), Observers Observed: Essays on Ethnographic Fieldwork (1983), at 121-56. to describe a case study of a course for newly appointed Brazilian magistrates which was structured to break away from the traditional format of judicial education courses. The case for experiential learning in Brazilian judicial education here analysed has as its theoretical framework36x Considering the lack of specialised literature on teaching methods that provide direct experiences of social realities for magistrates in judicial schools, the case study of initial judge training described here drew upon literature from three fields: pedagogy (Freire, above n. 20), anthropology (Holston, above n. 26) and philosophy (Koppensteiner, above n. 19). the works by Freire,37x Freire, above n. 22, at 213. Holston38x Holston, above n. 28, at 367. and Koppensteiner.39x Koppensteiner, above n. 21, at 567. Freire demonstrated the remarkable potential of his students when encouraged to be active participants in their own teaching and learning processes.40x Ibid. Taking this theoretical framework as starting point, Holston suggested in his ethnographic studies the pedagogical potential of encounters between ‘estranged citizenships’ and of one experiencing different social realities.41x Ibid. Years later, based on ten years of empirical studies, also inspired by Freire’s studies, Koppensteiner, posited the possibility of unveiling social structural violence through an instructional approach that incorporates the body, voice and movement.42x Ibid.

This pedagogical experiment was carried out in a Judicial School attached to a State Court in Southeast Brazil. This particular case study serves as a platform to examine the potential and obstacles associated with having judicial schools as a locus for developing innovative experiential teaching techniques aimed at changing the current ‘status quo’ within the judiciary and at addressing the problems that such status quo gives rise to.

The course described here was designed, intentionally, to make judges familiar – not only through theoretical discussions but through direct experience – with the diverse social realities their work will affect. The teaching team of this course ventured beyond facilitated dialogic sessions (‘classes’) to explore the transformative potential of interactions in real-world settings, involving experiences and direct engagement with marginalised communities and vulnerable populations. The next section presents in more detail the structuring of the course. -

3 Experiential Learning in Judicial Education: Chronicle of a Pioneer Course in Brazil

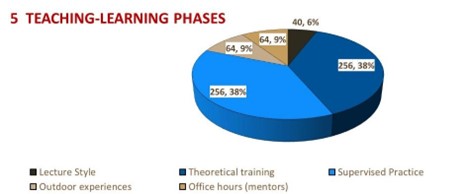

Illustrative graph of the distribution of the workload by teaching method used in training activity and the corresponding percentage in the total time of the course

The experiential learning activities herein described were designed as part of a mandatory course for recently appointed judges. In Brazil, judges are required to attend a series of lectures focused on both the legal theory and the more practical administrative and managerial aspects of their new position.43x As per the ENFAM regulations (02/2016). Usually, these lectures are delivered by more experienced colleagues who are invited to share their views on judicial activity.44x M.S. Oliveira. M.R.M. Veiga & R.P. Bacellar, ‘Teacher training in the scope of ENFAM: Practices, results and curricular perspectives’, Journal of the National School of Magistracy, at 14 (2015), https://www.enfam.jus.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/ArtigoMarizeteBacellarRaiRelatoFofo2015.pdf (last visited 9 March 2024).

This choice to charge more experienced peers to make the presentations has an important symbolic function and serves as a sort of rite of passage to the novices who are introduced to the ethos of the bench.45x Ibid. Traditionally, these courses are entirely made up of magisterial expositions taking place in auditoriums, classrooms or the precincts of the courts.

The course object of this article was conducted in 2022 at a Magistrate’s School in Southeastern Brazil and had a public of 51 newly appointed judges. The social profile of the group was markedly homogenous, with the overwhelming majority having come from the most well-off segments of Brazilian society.Out of the 51 participants, 39 (75%) had attended private46x See technical summary of the school census, https://www.gov.br/inep/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/censo-escolar/mec-e-inep-divulgam-resultados-do-censo-escolar-2023 (last visited 9 March 2024). The best grades of those who studied in the best schools – usually private – guarantee places in higher education in public universities. elementary schools; 37 (71%) went to private high schools; and 30 (59%) obtained their degrees in public universities, which are deemed to be elite and have highly competitive entrance tests. Only 4 participants (7%) had studied all their lives at the problem-ridden public education system. There were only 11 women among the new group and no more than 5 participants self-identified as individuals of African descent. This composition of the group stands in stark contrast with the composition of the Brazilian population. Far from being surprising, this homogeneity is a longstanding, permanent feature of the Brazilian judiciary.

The new dynamics designed for this course (namely, experiential learning) aimed at tackling the adjudicative bias likely to spring from this rather monolithic group. The pedagogical goal was twofold: (1) to enhance the group’s awareness of its homogeneity and its potential impact on their work as judges and (2) to allow the group to have direct, first-hand experience of a variety of social settings located in the jurisdiction of the court. This proposal included visits to different places and opportunities to engage in a dialogue with the communities living there.47x The external visits included: (1) technical visit to the Palace of Justice of the Capital; (2) Gericinó Penitentiary Complex; (3) Degase – Youth Detention Unit; (4) Benfica Custody Hearing Centre; (5) Justice on Wheels Programme; (6) Amazon exhibitions at the Museum of Tomorrow; (7) Public Defender’s Office and conversations with victims of state violence; (8) the complex of police stations and training centre ‘Police Town’; (9) Child Reception Centre – for abandoned children and the I and II Courts of Childhood, Youth, and the Elderly; (10) Centre for Domestic and Gender-based Violence Assistance, where conversations with feminist movement representatives took place; (11) Centre for Alternative Dispute Resolution and Citizenship (CEJUSC); (12) ‘Little Africa’ circuit with the history of slavery told by Black historians in the city streets; (13) Playful games and discussion circle with the youth of favelas in a Social Circus, https://www.emerj.tjrj.jus.br/paginas/magistrados/curso-oficial-de-formacao-inicial-para-magistrados/legislacao.html (last visited March 2024).

This novel pedagogical perspective was presented by representatives of the teaching team to the Board of the Judicial School, which approved the experiment. The teaching team included experienced judge-instructors with a strong commitment to enhance the capacity of the judiciary to serve as an effective instrument for social transformation. The team was coordinated by two judges and two justices, while eight assistant judges monitored, mentored and evaluated the performance of the new colleagues throughout the course.

The initial task undertaken by the team was to adapt and update the mandatory topics outlined in the National Judicial School regulations. As per the ENFAM regulations (02/2016), the official initial training for magistrates has a minimum of 480 hours, distributed over a 4-month full-time schedule (8 hours daily). The mandatory curriculum includes: (1) 40 hours of instruction provided by ENFAM; (2) a minimum of 200 hours of instruction by the local judicial school; and (3) the remaining 240 hours to be utilised for a practical internship with more experienced judges.

As can be seen in Figure 1, the training hours exceeded the mandatory minimum of 480 hours. This surplus was necessary to allow for outdoor experiential activities and informal mentoring sessions led by experienced judges.

Abiding by these directives, the teaching team proposed four formation modules: Module 1: Jurisdiction, practical aspects; Module 2: Management, practical aspects; Module 3: Ethics and Fundamental Rights Assurance; and Module 4: Vision of the Future. Modules were structured mostly following the traditional methodology of lectures by peers (91% of the teaching hours) as the team considered that maintaining a degree of continuity would help diminish potential resistance to the activities based on the new methodology of outdoor experiential activities (9% of teaching hours).

The practical implementation of this new methodology was rather challenging. Once a week, the judges would leave the premises of the judicial school and embark on an excursion called ‘outdoors experiential activities’. For safety reasons, the court to which the judicial school was attached ordered that a strict logistical and security protocol be followed when judges were taken out of the courtroom. A team of the Military Police, working with intelligence agencies from the State where the course took place, needed to be previously informed of the locations of technical visits and to approve them.

In addition to these requirements, a second and important challenge was the number of students (51). When such a large group arrived at the locations, it invariably caused a commotion, which was amplified by the fact that the visitors were representatives of the judiciary and were ostensibly protected by the police. This dynamic – an inescapable consequence of the protocol required by the court – represented a serious limitation to the desired immediacy of the exchange with the communities.

To try to mitigate this problem, the class was typically divided, for external activities, into two groups of participants, each with a judge-auxiliary responsible for supervising the activity. Two or more different locations were coordinated by proximity to ensure that the activities of each group occurred in parallel and, subsequently, crossed over: for example, while group A was in the female prison, group B would be in the male prison, and then they would switch.

The locations visited were related to the topics studied in theoretical classes during the week. The locations in Module 1 – Jurisdiction and Practical Aspects – were more institutional in nature: judicial emergency services, the monitoring room of the judiciary’s inspection body, and a juvenile detention facility.

In Module 2 – Management and Practical Aspects – the new magistrates were introduced to the facilities and services of a Custodial Hearing Centre which operates in a public prison; they talked to participants of a programme named Justice on Wheels.48x See footnote 60. The new judges also engaged in a roundtable at the Public Defender’s Office with the presence of defenders working in cases involving fundamental rights. Finally, they visited a museum to view an exhibition by photographer Sebastião Salgado about the Amazon and Possible Futures.

In Module 3 – Ethics and Fundamental Rights Guarantees – the magistrates visited the complex of police stations and training centre named ‘Police Town’. They also visited a Child Reception Centre (for abandoned children and victims of abuse) and the women’s protection network – the Women’s Assistance Police Station and the Women Victims of Violence Centre. Finally, they participated in a roundtable discussion with women who acted as representatives in the Constituent Assembly – Brazilian suffragettes – who had helped include women’s rights in the Federal Constitution.

For the final module, Module 4 – Vision of the Future – the magistrates visited the Centre for Alternative Dispute Resolution and Citizenship (CEJUSC), where they participated in an experience of Nonviolent Communication and Conflict Mediation. Additionally, the module included what was arguably its most unusual experiential activity: a visit to a local Social Circus located in the city’s lower HDI area. The goal was to allow judges to engage in playful circus activities with the community, to help them see each other from a novel angle and to understand the complexities and connections of their different realities. Judges were also invited to a roundtable discussion with children and teenagers from local communities and favelas.

The micro relationships among new judges themselves and the teams of employees and collaborators involved in this judicial training were also designed to be educative in terms of affective dialectics and more horizontal interactions, oriented to build democratic institutions.49x N. Koppensteiner, above n. 19, at 487. Drawing inspiration from Freire, above n. 20, Koppensteiner, above n. 19 conducted pedagogical experiments and proposed five systematised categories of knowledge: (1) somatic knowledge through the body (sensation) – the senses; (2) empathic and emotionally moving knowledge through the heart (feeling) – emotions; (3) intellectual knowledge through the mind – the rational mind (intellect); (4) intuitive knowledge through the soul – what he refers to as intuition – serving as a congruence of the preceding three categories; and lastly, (5) transpersonal knowledge through the spirit – what he terms ‘witnessing’ – representing the expansion of the prior congruence into a broader sphere, which we may describe as community. Koppensteiner, above n. 19, at 567.

Horizontal interactions are particularly important in this context once judges, upon assuming their roles in the bench, tend to ‘lose their nominal identity’. They will now be called not by their names but by the honorific title ‘Your Honour’. The repeated assertion of their ‘excellence’ – in Portuguese ‘Vossa Excelência (Your Excellence)’ can, throughout their careers, distance magistrates from their humanity in their work routines: their vulnerabilities, feelings and inherent human sensations.

In order to tackle this risk, several treatment protocols were altered during the training. The new judges were not called ‘Your Excellency’ before their graduation date but rather by their names, preceded by ‘Dr.’ or ‘Judge’. This postponed the introduction of the honorific title ‘excellency’. Throughout the course, the continuous assistance magistrates usually receive from the court staff, even for ordinary matters unrelated to their judicial function, was diminished, as a means to build an awareness of the body-space-environment relationships, break hierarchical social structures and humanise social interactions with the staff, their surroundings and themselves.50x Ibid.

This approach encouraged bodily movement and care for colleagues, the workspace and collaborators – the labour ecosystem. Practices such as fetching their own water, washing cups and organising their schedules were established – an apparently lesser aspect but which was novel and embodied a powerful message in the heavily hierarchical context of Brazilian judicial education. The new judges were also invited to be always supportive of their colleagues and of the supporting personal; to get involved in activities such as keeping track of who has yet to arrive for the van or tour group; remembering to return to the classroom to pick up their own trash; managing their own administrative documentation related to their tenure; and expressing gratitude to drivers, security personnel and catering staff each day of class, all of these were part of the training environment. This ethos caused some discomfort among the judges who had previous experience of being ‘served as judges’ and thus came to see it as natural that several everyday tasks be taken care of by the staff.

The new ethos soon made the destabilising nature of the new methodology very clear. The weekly external visits – and their implied demand that judges step outside their known territories and their social and intellectual comfort zones – were vocally criticised by some of the participants: ‘Do they want to make judges look like fools?’ Given this criticism, the Board of the Judicial School determined that the activity at the Social Circus would be optional. A group of 12 new judges chose to experience this new setting, while the remaining 39 opted for the alternative activity that was offered: a lecture on ethics delivered by a Minister of the Superior Court of Justice.

This backlash against the new methodology seems to point out to a deeply rooted representation that Brazilian magistrates have of their function and the role of the judiciary. The final section of this article will discuss this claim in more detail. The next section presents the perception of participants in their own words. -

4 In Their Own Words: Participant’s Views on Experiential Learning and the Novel Course

The judicial academy’s faculty conducted a survey among approximately 1,000 judges and appellate judges to gauge their preferences on course delivery, essential topics for judicial competency, and the value of non-traditional instructional settings. A sizable majority of the judges in the judicial school where the novel training took place (70%) approved of having classes held outside the traditional classroom setting and acknowledged the potential of experiential learning for magistrate training.

Of this group, 25% advocated for this instructional format unequivocally, asserting that ‘out-of-classroom lessons are essential for cultivating competent magistrates, regardless of the subject matter.’ Meanwhile, 55% of the same group believed that the need and desirability of external classes was dependent ‘on the topic being studied’. At the same time, 30% of the whole group saw no need at all for judges to partake in practical classes outside the courtroom.51x Ibid.

The testimonials on those institutional visits that required limited interaction with the public usually offered standard praise for the institutional ethos or the magistrate’s own ethos:52x The testimonials we are taking from the court’s newsletter articles published at the official website of the judicial school where the training took place.‘I attended the School of Magistracy, completed internships in civil, criminal, and youth courts, and the experience in this Initial Training Course, the contact with experienced judges and justices, is proving to be very beneficial.’53x Original version: ‘Eu estou muito feliz por ser aprovado nesse concurso, inicialmente, por ser meu estado de origem, e principalmente por uma questão familiar – a minha companheira é juíza de Direito aqui no Rio de Janeiro, e tenho uma filha e um enteado pequenos –, então era imperioso esse retorno para casa’, https://site.emerj.jus.br/noticia/543 (last visited 10 March 2024).

However, when there was direct interaction between magistrates and the public (e.g. juvenile offenders), there was a distinct change in the tone of the testimonials, which became much more personal and emotional: ‘No book or manual teaches a judge how to be a judge … spending time in this facility is very important’;54x Original version: ‘Nenhum livro ou manual, ensina o juiz a ser juiz. Ele precisa, quando vem para uma Vara da Infância Infracional, entender o que é o adolescente infrator, saber a história dele, ter empatia e saber para que lugar vai encaminhar o adolescente, caso aplique uma medida socioeducativa de internação’ https://site.emerj.jus.br/noticia/616 (last visited 10 March 2024). ‘it was one of the most stunning experiences of my life to see the situation of these kids’;55x Ibid. Original version: ‘Foi uma das experiências mais impactantes da minha vida ver a situação dos menores’. ‘looking into their eyes, seeing that they have lives, they are people, human beings. My hope is that all of us who had this experience do not forget this’;56x Ibid. Original version: ‘Olhar nos olhos deles, ver que são vidas, que são pessoas, seres humanos, que estão por trás daqueles processos. A minha esperança é que todos nós que tivemos essa experiência não esqueçamos disso: que são pessoas por trás daqueles processos e da importância que tem a nossa função dentro dessa realidade, dentro desse sistema’. ‘Most of them did not know their father’; ‘These visits are important to create a bond among the newly appointed judges’; ‘It is very important for us who are entering the judiciary to understand the limitations of the State because the ECA [the legislation] outlines a series of guidelines, but in practice, the State does not implement them. Therefore, it is necessary that … we try our best to adapt and enforce the law.’57x Ibid. Original version: ‘É muito importante para nós que estamos ingressando na magistratura saber das limitações do Estado, porque o ECA traz uma série de diretrizes que têm que ser seguidas, mas na prática o Estado não implementa. Então, é necessário que tenhamos consciência da forma como se dá o sistema, das limitações, para que tentemos ao máximo adaptar aquilo e fazer cumprir a lei’.

In addition to expressing surprise and using terms related to bodily sensations – ‘breathing; looking into their eyes’ – and emotions – ‘impactful; hope’, the judges also reported a sense of complicity and ‘bond’58x Ibid. ‘these visits are important to create a bond among the newly appointed judges’; Original version: ‘Essas visitas são importantes para criar um vínculo entre os juízes empossados.’ form among them, a trait that is often seen among those who go through a shared experiential learning process. Finally, many voiced their concern about ‘adapting’ and taking the necessary steps to protect fundamental rights in a ‘State that falls short of guaranteeing them’.59x Ibid.

The visit to the Justice on Wheels60x Justice on Wheels Programme emerged as a new paradigm for the delivery of judicial services in which judges, along with members of the Public Defender’s Office, meet with citizens, especially those most in need or less privileged due to the lack of efficient public policies in certain areas of our State. In fact, it is a pioneering, practical and accessible programme, especially for citizens who face greater difficulty in accessing public services. Among its services are guaranteeing transgender individuals’ rights to change their name and gender change, https://www.tjrj.jus.br/institucional/projetosespeciais/justicaitinerante (last visited 10 March 2024). stood out for testimonials that expressed surprise and interest: ‘It was my first experience with the itinerant court … This opens up a new reality … the contact with the population, being able to talk and see the social issues that exist … I felt very eager to participate and work in the itinerant court’; ‘The invisibility of conflicts, pain, and issues that these people have. When you go “itinerating”, you discover these needs of the population’;61x Original version: ‘Foi minha primeira experiência com a Justiça Itinerante…. Isso abre uma nova realidade, mostra a importância de termos contato com a população, de poder conversar e ver os problemas sociais que existem, além de ver na prática o problema. Eu fiquei com muita vontade de participar e de atuar na Justiça Itinerante’; ‘Invisibilidades dos conflitos, das dores e das questões que essas pessoas têm. Quando você vai ‘itinerant’, você vai descobrindo essas necessidades da população’, https://site.emerj.jus.br/noticia/639 (last visited 10 August 2023). ‘When the judicial bus, along with the Public Ministry and the Public Defender’s Office, enters [the favelas], solving a problem on the spot, it has the power of social and personal transformation, not only for the person being served but primarily for us, the participants in the justice system.’62x Original version: ‘Quando o ônibus do Judiciário, do MP [Ministério Público] com a Defensoria Pública, entra no Jardim Catarina, na Maré, no Complexo do Alemão, resolvendo um problema na hora, isso tem um poder de transformação social e pessoal, não só para a pessoa atendida, mas principalmente para os integrantes do sistema de justiça’, https://site.emerj.jus.br/noticia/677 (last visited 10 August 2023).

At the Public Defender’s Office63x https://site.emerj.jus.br/noticia/833 (last visited 10 August 2023). and the Custodial Hearing Centre, the statement by the Public Defender General clearly underscored the need to hear the voice of these institutional actors: ‘it was the first time that judges had visited the headquarters of the Public Defender’s Office to listen to them. For us, to receive magistrates at the Public Defender’s Office is something historic not only for the Public Defender’s Office but for the entire justice system.’64x Ibid. Original version: ‘Nós recebermos magistrados e magistradas na Defensoria Pública é algo histórico não só para a Defensoria, mas para o sistema de justiça’.

The testimonials from crime victims who had been represented by the Public Defender’s Office reveal the impact of the encounter itself: ‘It’s beautiful to see this youth [new magistrates] going further and with a huge commitment to take responsibility [for the actions they will take as judges], like the one you will have from now on, with the actions,’65x Ibid. Original version: ‘É lindo ver essa juventude chegando cada vez mais longe e com compromisso enorme de ter uma responsabilidade, como a que vocês vão ter a partir de agora, com as ações.’ said a victim of political violence. Her speech at the roundtable, which detailed the history of human rights activism of her murdered daughter, caused a profound silence to fall upon the assembly of new judges.66x The mother of the murdered councilwoman Marielle Franco, emblematic political crime with international repercussions, whose sister is currently the Minister of Racial Equality in Brazil in the Lula government.

At the roundtable discussion with women who participated in the Constituent Assembly – and advocated for the inclusion of women’s rights in the Federal Constitution, testimonials reinforced this perception of the importance for judges to listen to the population whose lives their work will touch: ‘It is very important that we judges practice listening. We have to give voice [to these women], we must take into account their testimonies, we cannot assume that [a] woman is lying [because she is a woman], that her testimony is suspect. The judge is there to listen.’67x Ibid. Original version: ‘É muito importante que nós juízes tenhamos o exercício de escuta. Nós temos que dar voz [para essas mulheres], devemos levar em conta o seu depoimento, não podemos partir do pressuposto que aquela mulher está mentindo, que o depoimento dela é suspeito. O juiz está ali para ouvir’.

The reactions from magistrates who had the opportunity to play with children from the poor communities and favelas of the city and engage in conversation with them were among the most emotional: ‘It was the best visit!’; ‘It was the best visit!’68x https://site.emerj.jus.br/noticia/856 (last visited 10 August 2023). (the most repeated phrase);There is no such thing as judges being isolated from society; judges must receive people in various situations. Some judges are isolating themselves … that can’t be. Judges must be close to society to understand case by case. That’s why I tell my younger colleagues: don’t isolate yourself … otherwise, we end up living in a world we don’t know.69x Ibid. Original version: ‘Não existe o juiz estar afastado da sociedade, o juiz tem que receber as pessoas em diversas situações. Hoje em dia nós vemos o home office, que facilitou o trabalho dos juízes em casa, só que tem juiz se enclausurando, que não vai mais no Fórum. Isso não existe’; ‘O juiz tem que estar próximo da sociedade para entender caso a caso, por isso eu falo para os colegas que são mais novos: não se enclausure… se não nós acabamos vivendo em um mundo que nós não conhecemos’.

The enthusiastic quotes, like the one above, and the positive perceptions some of the participants had of the experiential learning approach were in stark contrast with the often silent disapproval of this pedagogical choice by a large part of the cohort. The fact that the Board of the Judicial School changed the status of some of the planned visits from mandatory to optional bespeaks an institutional position that seems, at least in part, ready to accommodate this disapproval. Moreover, some high-level administrators (senior judges and justices) of that court did not view the innovations favourably, expressing disapproval in private. The few innovative practices, comprising less than 10% of the training curriculum, were enough to split opinions.

The reasons for both the enthusiasm and disapproval with which this course was greeted are arguably manifold and complex. The findings of the present study suggest that a key component of these antinomic reactions lies in competing visions of the role of judges and judiciary in Brazil. These clashing perceptions have deep practical and theoretical implications and are part of a broader movement of challenging up-to-now hegemonic views on Brazilian society and the role that law plays and should play in it. -

5 Conclusion

This article argues that the social background of members of the judiciary significantly influences their professional performance. When this social background is markedly homogeneous and elite – as is the case in Brazil – it can work to lessen the social legitimacy of courts, which become vulnerable to being seen as class-biased and out of touch with the lives of ordinary people. The worldview developed by members of dominant social classes, concerning society as a whole and the legal system in particular, tends to diverge markedly from that of less privileged groups. Homogeneity can also diminish judges’ incentives to improve their legal reasoning, as their socially embedded understanding of crucial legal concepts (e.g. average person, ‘reasonableness’, ‘proportionate means’ and ‘average person’) tends to be seen as ‘default’ or ‘normal’ (thus, normative) when replicated by likeminded colleagues.

The experience expounded in this text outlines a novel approach to judicial education that seeks to challenge the insularity that traditionally separates the judiciary from the population in Brazil. This initiative endeavoured to prompt reflection on the multifaceted implications of this separation. It represented a pioneering effort to encourage magistrates to gain first-hand familiarity with a variety of living experiences and develop an awareness of the tangible realities within their jurisdictions, while simultaneously comprehending the nuances of diversity therein.

While Paulo Freire’s educational method was originally developed and applied to impoverished communities, under the assumption of their alienation and underprivileged status, an examination of the judges’ worldviews resulting from their prior life experiences sheds light on the potentially alienating nature of the modus vivendi and education of the elite in Brazil. In this sense, this article holds the applicability of Freire and his theoretical successors, such as Holston and Koppensteiner, not only to the marginalised but also, and perhaps primarily, to the elite.

The article outlined the strategic efforts to implement innovative external classes in a judicial school. The experiment of external classes, which comprised a small percentage (9%) of the total course curriculum, revealed institutional barriers to experiential learning.

Cognitive structures and power dynamics are intrinsically intertwined and dialectically interdependent. From a theoretical standpoint, the potential detachment of magistrates from the surrounding reality directly affects their understanding of the law and its social function. The theoretical disputes between neo-constitutionalists and neo-positivists, which characterise the contemporary Brazilian legal landscape,70x O.V. Veira and R. Glezer, The reason and the vote: constitutional dialogues with Luís Roberto Barroso (2017), at 74. can only be comprehended within the context of this insularity and the competing interpretations thereof.

Holston71x Ibid. observes that for every insurgency (or disruptive innovation of the status quo), there is a corresponding counterflow entrenchment (or conservatism) equally potent as the insurgency. Some high-level administrators of the judiciary did not view the innovations in power dynamics and proximity to citizens favourably. The few innovative practices, comprising less than 10% of the training curriculum, were sufficient to polarise opinions.

The experience recounted in this text presents a novel approach to judicial education, aimed at challenging the gap that traditionally separates the justice system from the population and magistrates from those under their jurisdiction. It represented a pioneering initiative, inviting judges to gain awareness of tangible realities within their jurisdictions. It is posited that these resistances to change constitute valuable evidence supporting the continued and enhanced pursuit of judicial education projects with the aim of problematising entrenched hierarchical perspectives. -

1 E.C. Alves, ‘Judicial Schools’. Journal of the National School of Magistracy, v.01, n. 2, at 19 (2006). Justice Eliana Calmon Alves is the first woman appointed to the Superior Court of Justice, where she held the position of Minister from 1999 to 2013. Online at: https://bdjur.stj.jus.br/jspui/handle/2011/1991.

-

2 B.S. Santos. For a Democratic Revolution of Justice (2008).

-

3 A. Boigeol, ‘The Training of Magistrates: From Practical Learning to Professional Schooling’, Ethics and Political Philosophy Magazine, at 70 (2010).

-

4 https://www.gov.br/inep/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/censo-escolar/mec-e-inep-divulgam-resultados-do-censo-escolar-2023 (last visited 9 march 2024).

-

5 M.A. Salvato, P.C.G Ferreira & A.J.M. Duarte, ‘The Impact of Education on Income Distribution’, Economic Studies, v. 40, n. 4, at 795 (2010). Online at: https://www.scielo.br/j/ee/a/LKVPvzm7PdJcbqF7PxY5dsq/?format=pdf&lang=pt.

-

6 National Council of Justice (CNJ), Ethnic-Racial Diagnosis of the Judiciary (2023), at 20.

-

7 National Council of Justice (CNJ), Report on Female Participation in the Judiciary (2023), at 13.

-

8 National Council of Justice (CNJ), Judiciary in Numbers (2023), at 37.

-

9 https://www12.senado.leg.br/institucional/responsabilidade-social/oel/panorama-national/Brazilian-population (last visited 9 March 2024).

-

10 In Brazil, 46% of the judges are White male, 34% White female and only 14% of are Black African descendants, https://www.cnj.jus.br/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/justica-em-numeros-2023-010923.pdf (last visited 9 March 2024).

-

11 This bias seems to remain dominant in present-day Brazil, unscathed by decades of scholarly and political criticism. President Lula, widely considered as a progressive politician, has appointed two men for the Supreme Court, one of them to replace one of the two women justices in STF. The Court is currently composed of 10 men and 1 woman, all White, https://brazilian.report/liveblog/politics-insider/2023/09/17/brazilians-female-supreme-court-justices/ (last visited 9 March 2024).

-

12 Brazilian Supreme Court (STF). List of Ministers, https://portal.stf.jus.br/ostf/ministros/ministro.asp?periodo=STF&consulta=ANTIGUIDADE (last visited 9 March 2024).

-

13 F.C. Fontainha and P.G. Barros, ‘The Brazilian public tender and the selection process ideology’. Legal Review of the Presidency, at 780 (2015).

-

14 https://www.cnj.jus.br/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/diagnostico-etnico-racial-do-poder-judiciario.pdf (last visited 9 March 2024).

-

15 The National Council Regulation 540/2023 provides for gender parity, with an intersectional perspective on race and ethnicity, in administrative and jurisdictional activities within the scope of the judiciary, https://atos.cnj.jus.br/atos/detalhar/5391 (last visited 9 March 2024).

-

16 ‘The establishment of judicial schools in Brazil played a pivotal role in equipping judges to confront contemporary exigencies, facilitating their adaptation to the evolving landscape of legal interpretation and furnishing them with ongoing updates and practical instruction. The enactment of Constitutional Amendment No. 45/2004 served as a landmark, accentuating the significance of judicial academies and mandating the establishment of the National School for the Training of Magistrates (ENFAM).’ E.C. Alves, ‘Judicial Schools’, Journal of the National School of Magistracy, at 19 (2006).

-

17 M.S. Oliveira. M.R.M. Veiga & R.P. Bacellar, ‘Teacher Training in the Scope of ENFAM: Practices, Results and Curricular Perspectives’, Journal of the National School of Magistracy, at 14 (2015), https://www.enfam.jus.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/ArtigoMarizeteBacellarRaiRelatoFofo2015.pdf (last visited 9 March 2024).

-

18 As per the ENFAM regulations (02/2016), the local judicial school is responsible for implementing local training for judges in accordance with ENFAM’s regulations, https://emarf.trf2.jus.br/site/documentos/resolucaoenfam022016.pdf (last visited 9 March 2024).

-

19 N. Koppensteiner, Transrational Methods of Peace Research: The Researcher as (Re)source (2020), at 567.

-

20 P. Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed (2005), at 76.

-

21 O.V. Veira, Supremocracy (2008), at 441-63, https://doi.org/10.1590/S1808-24322008000200005 (last visited 9 March 2024).

-

22 Ibid.

-

23 Ibid.

-

24 M.R. Veiga, M.S. Oliveira & S. Rauchbach. ‘Teaching Planning in the Context of the Judiciary: Theoretical-Practical Pathways’, Journal of the National School of Magistracy, at 54 (2014), https://www.enfam.jus.br/wp-content/uploads/2015/02/Livreto-I-Curso-Planejamento-de-Ensino-Final3jun14.pdf (last visited 9 March 2024); Also, D.E. Cowdrey, ‘Teaching New Judges What It Means to “Be” a Judge’, Internation Organization for Judicial Training, at 54 (2020), https://academic.oup.com/book/32069/chapter-abstract/267878946?redirectedFrom=fulltext (last visited 9 March 2024).

-

25 Ibid.

-

26 The judicial school where the experience described herein took place conducted an initial diagnosis of the profile of the participating judges in the initial training course. In the sample, 71% (37) of the judges live and/or know only the South Zone and Barra da Tijuca areas scoring the best HDI of the city – home to the upper-middle and upper-class populations. Additionally, almost 80% of the new judges either do not use public transportation or use individual transport such as cars and taxis. According to Holston, in Brazil, it is a recognised fact that an unspoken form of apartheid exists, characterised by various facets of spatial (urban) and institutional segregation. And to go beyond this apartheid requires urban circulation and the meeting of antagonistic patterns of civilities. J. Holston, Insurgent Citizenship: Disjunctions of Democracy and Modernity in Brazil (2013), at 367.

-

27 Ibid.

-

28 S.B. Blix , Making Independent Decisions Together: Rational Emotions in Legal Adjudication. Symbolic Interaction. (2021), at 23.

-

29 Ibid.

-

30 K. Luise, S. Gonçalves, T. Wurster & R.B. Ginsburg, Diversity in the Judiciary as a Prerequisite for Legitimacy (2020).

-

31 D.E. Cowdrey. ‘Teaching New Judges What It Means to “Be” a Judge’, International Organization for Judicial Training, at 54 (2020), https://academic.oup.com/book/32069/chapter-abstract/267878946?redirectedFrom=fulltext (last visited 9 March 2024).

-

32 ‘The absence of diversity within the group of magistrates implies the construction of a standard and universal rationality, formed from similar experiences and disconnected from the plurality and diversity present in society.’ K. Luise, S. Gonçalves, T. Wurster & R.B. Ginsburg, Diversity in the judiciary as a prerequisite for legitimacy (2020), https://www.ajufe.org.br/imprensa/artigos/15413-ruth-bader-ginsburg-e-a-diversidade-na-justica-como-pressuposto-de-legitimidade (last visited 9 March 2024).

-

33 Ibid.

-

34 Ibid.

-

35 J. Clifford, ‘Power in Dialogue in Ethnography’, in G.W. Stocking, Jr. (ed.), Observers Observed: Essays on Ethnographic Fieldwork (1983), at 121-56.

-

36 Considering the lack of specialised literature on teaching methods that provide direct experiences of social realities for magistrates in judicial schools, the case study of initial judge training described here drew upon literature from three fields: pedagogy (Freire, above n. 20), anthropology (Holston, above n. 26) and philosophy (Koppensteiner, above n. 19).

-

37 Freire, above n. 22, at 213.

-

38 Holston, above n. 28, at 367.

-

39 Koppensteiner, above n. 21, at 567.

-

40 Ibid.

-

41 Ibid.

-

42 Ibid.

-

43 As per the ENFAM regulations (02/2016).

-

44 M.S. Oliveira. M.R.M. Veiga & R.P. Bacellar, ‘Teacher training in the scope of ENFAM: Practices, results and curricular perspectives’, Journal of the National School of Magistracy, at 14 (2015), https://www.enfam.jus.br/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/ArtigoMarizeteBacellarRaiRelatoFofo2015.pdf (last visited 9 March 2024).

-

45 Ibid.

-

46 See technical summary of the school census, https://www.gov.br/inep/pt-br/assuntos/noticias/censo-escolar/mec-e-inep-divulgam-resultados-do-censo-escolar-2023 (last visited 9 March 2024). The best grades of those who studied in the best schools – usually private – guarantee places in higher education in public universities.

-

47 The external visits included: (1) technical visit to the Palace of Justice of the Capital; (2) Gericinó Penitentiary Complex; (3) Degase – Youth Detention Unit; (4) Benfica Custody Hearing Centre; (5) Justice on Wheels Programme; (6) Amazon exhibitions at the Museum of Tomorrow; (7) Public Defender’s Office and conversations with victims of state violence; (8) the complex of police stations and training centre ‘Police Town’; (9) Child Reception Centre – for abandoned children and the I and II Courts of Childhood, Youth, and the Elderly; (10) Centre for Domestic and Gender-based Violence Assistance, where conversations with feminist movement representatives took place; (11) Centre for Alternative Dispute Resolution and Citizenship (CEJUSC); (12) ‘Little Africa’ circuit with the history of slavery told by Black historians in the city streets; (13) Playful games and discussion circle with the youth of favelas in a Social Circus, https://www.emerj.tjrj.jus.br/paginas/magistrados/curso-oficial-de-formacao-inicial-para-magistrados/legislacao.html (last visited March 2024).

-

48 See footnote 60.

-

49 N. Koppensteiner, above n. 19, at 487. Drawing inspiration from Freire, above n. 20, Koppensteiner, above n. 19 conducted pedagogical experiments and proposed five systematised categories of knowledge: (1) somatic knowledge through the body (sensation) – the senses; (2) empathic and emotionally moving knowledge through the heart (feeling) – emotions; (3) intellectual knowledge through the mind – the rational mind (intellect); (4) intuitive knowledge through the soul – what he refers to as intuition – serving as a congruence of the preceding three categories; and lastly, (5) transpersonal knowledge through the spirit – what he terms ‘witnessing’ – representing the expansion of the prior congruence into a broader sphere, which we may describe as community. Koppensteiner, above n. 19, at 567.

-

50 Ibid.

-

51 Ibid.

-

52 The testimonials we are taking from the court’s newsletter articles published at the official website of the judicial school where the training took place.

-

53 Original version: ‘Eu estou muito feliz por ser aprovado nesse concurso, inicialmente, por ser meu estado de origem, e principalmente por uma questão familiar – a minha companheira é juíza de Direito aqui no Rio de Janeiro, e tenho uma filha e um enteado pequenos –, então era imperioso esse retorno para casa’, https://site.emerj.jus.br/noticia/543 (last visited 10 March 2024).

-

54 Original version: ‘Nenhum livro ou manual, ensina o juiz a ser juiz. Ele precisa, quando vem para uma Vara da Infância Infracional, entender o que é o adolescente infrator, saber a história dele, ter empatia e saber para que lugar vai encaminhar o adolescente, caso aplique uma medida socioeducativa de internação’ https://site.emerj.jus.br/noticia/616 (last visited 10 March 2024).

-

55 Ibid. Original version: ‘Foi uma das experiências mais impactantes da minha vida ver a situação dos menores’.

-

56 Ibid. Original version: ‘Olhar nos olhos deles, ver que são vidas, que são pessoas, seres humanos, que estão por trás daqueles processos. A minha esperança é que todos nós que tivemos essa experiência não esqueçamos disso: que são pessoas por trás daqueles processos e da importância que tem a nossa função dentro dessa realidade, dentro desse sistema’.

-

57 Ibid. Original version: ‘É muito importante para nós que estamos ingressando na magistratura saber das limitações do Estado, porque o ECA traz uma série de diretrizes que têm que ser seguidas, mas na prática o Estado não implementa. Então, é necessário que tenhamos consciência da forma como se dá o sistema, das limitações, para que tentemos ao máximo adaptar aquilo e fazer cumprir a lei’.

-

58 Ibid. ‘these visits are important to create a bond among the newly appointed judges’; Original version: ‘Essas visitas são importantes para criar um vínculo entre os juízes empossados.’

-

59 Ibid.

-

60 Justice on Wheels Programme emerged as a new paradigm for the delivery of judicial services in which judges, along with members of the Public Defender’s Office, meet with citizens, especially those most in need or less privileged due to the lack of efficient public policies in certain areas of our State. In fact, it is a pioneering, practical and accessible programme, especially for citizens who face greater difficulty in accessing public services. Among its services are guaranteeing transgender individuals’ rights to change their name and gender change, https://www.tjrj.jus.br/institucional/projetosespeciais/justicaitinerante (last visited 10 March 2024).

-

61 Original version: ‘Foi minha primeira experiência com a Justiça Itinerante…. Isso abre uma nova realidade, mostra a importância de termos contato com a população, de poder conversar e ver os problemas sociais que existem, além de ver na prática o problema. Eu fiquei com muita vontade de participar e de atuar na Justiça Itinerante’; ‘Invisibilidades dos conflitos, das dores e das questões que essas pessoas têm. Quando você vai ‘itinerant’, você vai descobrindo essas necessidades da população’, https://site.emerj.jus.br/noticia/639 (last visited 10 August 2023).

-

62 Original version: ‘Quando o ônibus do Judiciário, do MP [Ministério Público] com a Defensoria Pública, entra no Jardim Catarina, na Maré, no Complexo do Alemão, resolvendo um problema na hora, isso tem um poder de transformação social e pessoal, não só para a pessoa atendida, mas principalmente para os integrantes do sistema de justiça’, https://site.emerj.jus.br/noticia/677 (last visited 10 August 2023).

-

63 https://site.emerj.jus.br/noticia/833 (last visited 10 August 2023).

-

64 Ibid. Original version: ‘Nós recebermos magistrados e magistradas na Defensoria Pública é algo histórico não só para a Defensoria, mas para o sistema de justiça’.

-

65 Ibid. Original version: ‘É lindo ver essa juventude chegando cada vez mais longe e com compromisso enorme de ter uma responsabilidade, como a que vocês vão ter a partir de agora, com as ações.’

-

66 The mother of the murdered councilwoman Marielle Franco, emblematic political crime with international repercussions, whose sister is currently the Minister of Racial Equality in Brazil in the Lula government.

-

67 Ibid. Original version: ‘É muito importante que nós juízes tenhamos o exercício de escuta. Nós temos que dar voz [para essas mulheres], devemos levar em conta o seu depoimento, não podemos partir do pressuposto que aquela mulher está mentindo, que o depoimento dela é suspeito. O juiz está ali para ouvir’.

-

68 https://site.emerj.jus.br/noticia/856 (last visited 10 August 2023).

-

69 Ibid. Original version: ‘Não existe o juiz estar afastado da sociedade, o juiz tem que receber as pessoas em diversas situações. Hoje em dia nós vemos o home office, que facilitou o trabalho dos juízes em casa, só que tem juiz se enclausurando, que não vai mais no Fórum. Isso não existe’; ‘O juiz tem que estar próximo da sociedade para entender caso a caso, por isso eu falo para os colegas que são mais novos: não se enclausure… se não nós acabamos vivendo em um mundo que nós não conhecemos’.

-

70 O.V. Veira and R. Glezer, The reason and the vote: constitutional dialogues with Luís Roberto Barroso (2017), at 74.

-

71 Ibid.

Erasmus Law Review |

|

| Article | Innovative Pedagogical Approaches in Judicial Education: The Case of a Pioneer Training Programme for Magistrates in Brazil |

| Keywords | judicial education, Brazilian judiciary, legitimacy of courts, teaching methods, diversity |

| Authors | Rafaela Selem Moreira en José Garcez Ghirardi |

| DOI | 10.5553/ELR.000266 |

|

Show PDF Show fullscreen Abstract Author's information Statistics Citation |

| This article has been viewed times. |

| This article been downloaded 0 times. |

Rafaela Selem Moreira and José Garcez Ghirardi, "Innovative Pedagogical Approaches in Judicial Education: The Case of a Pioneer Training Programme for Magistrates in Brazil", Erasmus Law Review, 4 (incomplete), (2023):

|

This article presents and discusses a pioneering experiment of judicial education in Brazil. The groundbreaking course herein described was based on experiential learning and involved creating opportunities for the new judges to have direct interaction with the socially challenged communities likely to be affected by their work on the bench. The pedagogical goal was to enhance judges’ awareness of the manifold problematic effects that come from the highly homogeneous, elite social background of the judicial corpus in Brazil. The findings suggest a tension between the judicial education proposal discussed in this article and the deeply rooted perspectives on the ethos of judges and the meaning of their education. This tension underscores the urgency of intensifying efforts to enhance the capacity of Brazilian judicial education to help judges broaden their sensitivity to social diversity and thus become better equipped to deliver socially and legally high-quality decisions. The theoretical framework for the present study on the topic of judicial education is based on Alves, ‘Judicial Schools’. Journal of the National School of Magistracy, Boigeol ‘The Training of Magistrates: From Practical Learning to Professional Schooling’, Ethics and Political Philosophy Magazine, Fontainha and Barros, ‘The Brazilian public tender and the selection process ideology’. Legal Review of the Presidency, Cowdrey, ‘Teaching New Judges What It Means to “Be” a Judge’, International Organization for Judicial Training, and the works of Freire, Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Holston, Insurgent Citizenship: Disjunctions of Democracy and Modernity in Brazil, and Koppensteiner, Transrational Methods of Peace Research: The Researcher as (Re)source are used as the basis for the topics of education and experiential learning. The case study adopts an ethnographic approach based on Clifford, ‘Power in Dialogue in Ethnography’, since one of the co-authors of this article took part in the experiment. |