-

1 Introduction

In the analysis of the first part1x M. Bottis, M. Papadopoulos, C. Zampakolas, P. Ganatsiou, ‘Text and Data Mining in Directive 2019/790/EU – Enhancing Web-harvesting and Web-archiving in Libraries and Archives’, 9 Open Journal of Philosophy, (2019). of this article on Text and Data Mining (hereinafter, TDM) in Directive 2019/790/EU, it was supported that TDM is treated by Directive 2019/790/EU on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (hereinafter, DSM) as a means for research and innovation that allows uses of copyrighted works as well as of non-copyrighted material that are not clearly covered by the existing Acquis Communautaire on exceptions and limitations to copyright, and especially on the exception or limitation to copyright for the purpose of scientific research.

The new Directive on Copyright in the DSM rules in its Article 3 the purpose-specific TDM as a mandatory exception to the rights provided for in Article 5(a) and Article 7(1) of Directive 96/9/EC, Article 2 of Directive 2001/29/EC and Article 15(1) of Directive 2019/790/EU, while in its Article 4 rules TDM as a mandatory exception to the rights provided for in Article 5(a) and Article 7(1) of Directive 96/9/EC, Article 2 of Directive 2001/29/EC, Article 4(1)(a) and (b) of Directive 2009/24/EC and Article 15(1) of Directive 2019/790/EU. In both Articles 3 and 4 of Directive on Copyright in the DSM there is no reference to Article 3 of Directive 2001/29/EC. Thus, TDM is not provisioned as an exception to the right of communication to the public of works and the right of making them available to the public. For this reason, any discussion on TDM as an exception to the right of communication to the public and the right of making available to the public is of limited value in consideration of the provisions of the new Directive on Copyright in the DSM. This, however, does not lead to the conclusion that TDM and the right of communication to the public through the use of hyperlinking on the Web is a subject of limited value. But this subject was analysed in the authors’ contribution2x See M. Papadopoulos, C. Zampakolas, P. Ganatsiou, M. Kanellopoulou-Bottis, Web Harvesting Is Ante Portas of Greek Public and Academic Libraries (2018), Conference paper submitted to the 24th Panhellenic Conference of Academic Libraries, PALC24, Larissa, available at: http://palc24.cs.teilar.gr/conference/el/programma.jsp?id=12 (last visited 1 July 2019). to the 24th Panhellenic Conference on Academic Libraries, and this analysis would suffice for the time being.

Therefore, in the following analysis we elaborate briefly on provisions in EU Copyright law that were discussed during the proposal for a new Directive on Copyright in the DSM as well as provisions that are included in the text of Articles 3 and 4 of the new Directive 2019/790/EU per TDM. The following analysis refers to Article 5(3)(a) of InfoSoc Directive and Article 6(2)(b) and 9(b) of Database Directive and explains why these articles in EU Copyright law could not cover TDM as its legal foundation in the existing – before Directive 2019/790/EU – ‘Acquis Communautaire’. It also refers to Article 5(a) and Article 7(1) of Database Directive as well as Article 2 of the InfoSoc Directive, which are included in the text of Articles 3 and 4 of Directive on Copyright in the DSM and to the ruling of which TDM is provisioned as an exception.

In addition, the following analysis presents legislation in very few EU Member States that pertains to TDM and preceded the rulings of Directive 2019/790/EU. These EU Member States are the United Kingdom, Germany, Estonia and France. There is, also, legislation in Greece that preceded Directive 2019/790/EU and that assigns the National Library of Greece with the responsibility to monitor and archive the Internet (harvesting and archiving of works that reside on the Internet) or other technology environment. To this end, the National Library of Greece has been assigned the tasks to undertake, allocate and coordinate actions for Web harvesting and Web archiving at the national level even before the pass of Directive on Copyright in the DSM.

Remarkable examples of digital legal deposit from EU Member States are also presented in this article. The most notable examples are the ones from the United Kingdom and Ireland, Germany, the Netherlands and France. The example of Australia is also presented later because it is one of the oldest and most successful worldwide. The National Library of Australia’s digital legal deposit is state of the art.

The execution of TDM for Web harvesting and archiving of works found on the Internet is based on algorithmic applications and information technology. It is thus an automated computational process, the precision of which depends on the evolution of algorithms and the software used for their implementation. Later in this article we make a reference to the most commonly used algorithms used in libraries for crawling and harvesting of works found online as well as for analysing their content with the aim of discovering new scientific knowledge from their analysis.

Finally, in the text of this article we will address General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) issues that pertain to TDM and the data subjects whose works have been harvested and/or archived by a library deploying TDM. -

2 The Provision of Article 5(3)(a) of InfoSoc Directive Could Not Cover TDM

The text of Recital 5 of Directive 2019/790/EU refers to research, innovation, education and preservation of cultural heritage. The EU legislature in Recital 5 of this new Directive on Copyright in the DSM makes a nuanced reference to Article 5(3)(a) of Directive 2001/29/EC (the InfoSoc Directive), which provides for non-mandatory exceptions or limitations to the reproduction right of Article 2 of the InfoSoc Directive as well as to the right of communication to the public of works and the right of making available to the public other copyrighted subject matter of Article 3 of the InfoSoc Directive.

According to Article 5(3)(a) of the InfoSoc Directive, Member States may provide for exceptions or limitations to the rights provided for in Articles 2 and 3 in the case of, among others, use for the sole purpose of illustration for teaching or scientific research, as long as the source, including the author’s name, is indicated, unless this turns out to be impossible and to the extent justified by the non-commercial purpose to be achieved. Not all EU Members have adopted the provision of Article 5(3)(a) of the InfoSoc Directive, and among those EU Members that have implemented this provision in their national law, there are significant differences in the texts and accorded protection of national laws.

The provision of Article 5(3)(a) of the InfoSoc Directive was rightfully deemed not to be a sufficient legal foundation for TDM. Specifically:

Under Article 5(3)(a) of the InfoSoc Directive, Member States may provide for exceptions and limitations in the case of use for scientific research. Article 5(3)(a) of the InfoSoc Directive allows Member States to provide for exceptions in the case of ‘use for the sole purpose of illustration for teaching or scientific research, as long as the source, including the author’s name, is indicated, unless this turns out to be impossible, and to the extent justified by the non-commercial purpose to be achieved’. This exception is optional in ‘Acquis Communautaire’, which means that the question of its implementation was left to Member States. As a result, Member States have different rules and regulations in this regard currently, and some countries, like Greece, the Netherlands and Spain, recognise no research exception at all.

While research is the exploration of a certain subject matter with a view to finding data or any other kind of information or to gain knowledge, ‘scientific’ research must be carried out in a methodological and systematic way. The beneficiaries of the exception or limitation for scientific research provisioned in Article 5(3)(a) of the InfoSoc Directive are primarily professors, researchers and students at universities and similar institutions, but may also be others, such as practising lawyers or medical doctors when they carry out scientific research in order to write an article or inquire about the state of the art; even private persons may be beneficiaries if they carry out research according to scientific methods.3x M. Walter, S.V. Lewinski, European Copyright Law – A Commentary (2010), at 1043.

The most important use as regards scientific research is the reproduction of materials (see Article 9(2) of the Berne Convention) and, possibly, the making available of material online.4x Ibid. Broadcasting or other traditional forms of communication to the public hardly seem relevant in practice for uses of scientific research. The Berne Convention and other international laws do not allow for a limitation of the right of communication to the public, including broadcasting, for the purpose of scientific research; Article 10(2) of the Berne Convention addresses only teaching, and the three-step test of Article 9(2) refers only to the reproduction right. Therefore, Article 5(3)(a) of the InfoSoc Directive must be interpreted in light of the international copyright law, and the term ‘use’ is thus to be understood as not including any communication in traditional form. Consequently, the provision of Article 5(3)(a) of the InfoSoc Directive does not allow for exceptions and limitations of the right of communication to the public (Directive 2001/29/EC)5x Art. 3(1) of the InfoSoc Directive titled ‘Right of communication to the public of works and right of making available to the public other subject-matter’: Member States shall provide authors with the exclusive right to authorise or prohibit any communication to the public of their works, by wire or wireless means, including the making available to the public of their works in such a way that members of the public may access them from a place and at a time individually chosen by them. in traditional form.

In addition, the provision of Article 5(3)(a) of the InfoSoc Directive provides for the exception for ‘scientific research’ provided that it is the sole purpose of the use for which the exclusive rights may be restricted. Accordingly, when the reproduction or other use also fulfils an additional purpose, the exception or limitation does not apply.6x Walter and Lewinski, above n. 3, at 1044. Thus, all TDM projects that do not qualify as scientific research and/or have a commercial purpose, both direct or indirect economic or commercial advance, are excluded from the outset from the application of the exception of Article 5(3)(a) of the InfoSoc Directive.

Also, the exception of Article 5(3)(a) of the InfoSoc Directive applies only as long as the source, including the author’s name, is indicated. This condition corresponds to Article 10(3) of the Berne Convention, which specifies that the name of the author need be indicated only if it appears on the work used. The InfoSoc Directive is thus more demanding. At the same time, where the author has chosen to stay anonymous, there is no obligation to include his name – but rather a prohibition on doing so. Beyond the author’s name, the source includes the title of the work and the publishing house or the website from which the work or other subject matter was taken. The user is obliged to indicate the source provided that it does not turn out to be impossible. There are cases of legal impossibility, in particular where the author has chosen to stay anonymous and the mentioning of his name, if known to the user, would even violate his moral right. The InfoSoc Directive does not indicate what efforts must be made to find the author’s name or other indication of source before such indication may be considered impossible.

The use under Article 5(3)(a) of the InfoSoc Directive may be permitted only to the extent justified by the non-commercial purpose to be achieved. First, the use must aim to achieve a non-commercial purpose. This condition reflects the condition of Article10(2) of the Berne Convention that the use is compatible with fair practice, and to some extent it integrates the conditions of the three-step test. Recital 42 of the InfoSoc Directive clarifies that ‘non-commercial’ refers to the activity of teaching and research rather than to the organisational structure or the means of funding of the institution. Accordingly, a professor at a non-profit academic institution who writes a legal opinion for a company on payment of a fee carries out the related research for a commercial purpose and is thus not privileged by the exception of Article 5(3)(a). ‘Commercial’ should be read as including direct or indirect economic and commercial advantages. Also, such research must be strictly non-commercial (likely excluding mixed industry academic research, unless a sufficient separation of sub-projects is obtained), and must also indicate the source (including the author’s name) of each work used ‘unless this turns out to be impossible’. It is unclear whether such impossibility indeed exists for TDM research, where thousands, if not millions, of documents are involved.

From the wording of Article 5(3)(a) of the InfoSoc Directive, it is not sufficient that the use is to serve a non-commercial purpose; rather, it must also be justified by this purpose and is privileged only to the extent that it is thereby justified. This element again stems from Article 10(2) of the Berne Convention and has to be interpreted accordingly.7x Ibid., at 1045. -

3 The Provisions of Article 6(2)(b) and Article 9(b) of Database Directive Could Not Cover TDM

Aside from Article 5(3)(a) of the InfoSoc Directive, the provisions of Article 6(2)(b) and Article 9(b) of the Database Directive were rightfully deemed not to be a sufficient legal foundation for TDM. The EU legislature in Recital 5 of Directive 2019/790/EU on Copyright in the DSM makes a reference to the Database Directive, i.e. Directive 96/9/EC, and to the Computer Programs Directive, i.e. Directive 2009/24/EC. Specifically, and regarding the Database Directive:

Regarding Article 6(2)(b) of the Database Directive, it posits that Member States shall have the option of providing for limitations on the rights set out in Article 5 of the Database Directive in a number of strictly reported cases, among which is

‘… (b) where there is use for the sole purpose of illustration for teaching or scientific research, as long as the source is indicated and to the extent justified by the non-commercial purpose to be achieved.’

The rights provided to the author of a database in Article 5 of the Database Directive are the following:

The temporary or permanent reproduction by any means and in any form, in whole or in part;

The translation, adaptation, arrangement and any other alteration;

Any form of distribution to the public of the database or copies thereof. The first sale in the Community of a copy of the database by the rights holder or with his consent shall exhaust the right to control resale of that copy within the Community;

Any communication, display or performance to the public;

Any reproduction, distribution, communication, display or performance to the public of the results of the acts referred to in (b).

In consideration of the provision of Article 6(2)(b) of Directive 96/9/EEC, Member States may also exempt uses of a database for the sole purpose of scientific research from the protection of Article 5 of the Database Directive. Recital 36 of the Database Directive clarifies that whereas the term ‘scientific research’ within the meaning of this Directive covers both the natural sciences and the human sciences, the scientific research must be justified by a non-commercial purpose, which means that it must not aim at the achievement of any economic advantage.8x Ibid., at 734. The requirement for non-commercial purpose allows exemption from the protection conferred on the database author through Article 5 of the Database Directive even to uses of a database made by for-profit organisations or professionals provided that those specific uses are made for non-commercial purpose. Thus, the exemption is applicable provided that the pursued purpose of use of the database is non-commercial irrespective of the nature of the organisation or individual that made use of the database.9x Ibid., 734-5. When the use of the database is intended for commercial purpose, this use does not qualify for the exception of Article 6(2)(b) of the Database Directive regardless of the nature of the organisation or individual that carried out the use of the database. Thus, non-profit organisations such as academic (public) libraries that carried out TDM in the sense of use of a third party’s database aiming at commercial advantage, could not leverage on the provision of Article 6(2)(b) of Directive 96/9/EEC.10x Ibid., at 734.

Article 6(2)(b) of the Database Directive, apart from the indication of the source of a database, sets only one condition for the use of a database, namely that the research is justified by the non-commercial purpose to be achieved. The expression ‘to the extent justified by the non-commercial purpose’ implies the need for balancing the rights of the authors, on the one hand, and the interests of the general public, on the other. This balancing of the seemingly conflicting rights, namely the rights of the author of the database with the rights of the public, is required for the application of Article 6(2)(b) of the Database Directive in the sense that it is not sufficient that the use described in the said provision is possible or useful for non-commercial purposes; rather it must be ‘justified’ by such purposes, hence a proper balance between the conflicting rights must be achieved.11x Ibid., at 735. In that sense, TDM activities carried out by a library for scientific purposes could not find legal foundation under Article 6(2)(b) of the Database Directive unless the library can prove that it achieved a balance between the rights of the authors, on the one hand, and the interests of the general public, on the other.

Regarding the ‘use for the sole purpose of illustration for teaching’, the term ‘teaching’ is understood to be the same as in Article 10(2) of the Berne Convention and refers to education delivered by the teacher in public and/or non-commercial private schools, including secondary and vocational schools as well as universities.12x Ibid., 733-4. Teaching activity that aims at economic advantage – it is not necessary to achieve the intended economic advantage – could not leverage on the exemption of Article 6(2)(b) of the Database Directive. The exemption is permitted in favour of the teacher; the wording of the exemption refers to ‘teaching’ rather than ‘learning’ and thus cannot be interpreted so widely as to include in the meaning of the exemption every use of a database that is favourable to the learner/student. For this reason, use of a protected database in the framework of a test or of an examination is not covered by the provision of Article 6(2)(b) of the Database Directive because the examination occurs not in the framework of teaching but rather only after the teaching has been concluded. Examination usually occurs in the framework of evaluation of a student after the conclusion of teaching; it does not occur for the purpose of conveying new knowledge.13x Ibid., at 734.

All limitations under Article 6(2)(b) of the Database Directive must comply with the three-step test according to Article 6(3) of this Directive, which posits that in accordance with the Berne Convention for the protection of Literary and Artistic Works, Article 6 of the Database Directive may not be interpreted in such a way as to allow its application to be used in a manner that unreasonably prejudices the rights holder’s legitimate interests or conflicts with normal exploitation of the database. Article 6(3) of the Database Directive provides the three-step test as a safety net for the limitations provisioned in Article 6(1) & 6(2). Thus, the three-step test functions as the outer limit of the provisioned limitations, i.e. it is the yardstick used for delineating how far the limitations set through Article 6(1) & 6(2) of the Database Directive can go.14x Ibid., at 730.

Regarding the provision of Article 9(b) of the Database Directive that pertains to the extraction only – there is no wording for allowance of the reutilisation – where implemented, the substantial15x The notion of insubstantiality of a part of a database must be evaluated through quantitative and qualitative criteria. extraction16x In C-203/02, (2004), The British Horseracing Board Ltd and Others v. William Hill Organization Ltd., available at: http://curia.europa.eu/juris/liste.jsf?num=C-203/02 (last visited 1 July 2019) the CJ has clarified that the assessment upon the extraction or the reutilisation of the contents of a database must consider the investment in the creation of the database and the prejudice that the extraction or reutilisation cause to that investment. If there is a prejudice to the assessed investment there is infringement of the sui generis database right. of the content of a database is allowed for the purposes of illustration for teaching or scientific research; no act of reutilisation can be performed on the basis of Article 9(b) of the Database Directive. There is no exempted coverage for the use of a database or of its online transmission regarding the sui generis right.17x Walter and Lewinski, above n. 3, at 773. In this respect, the limitation to the sui generis right of the database maker is narrower than the limitation of Article 6(2)(b) on the copyright of the author of the database. This restriction, in effect, removes any practical value of the scientific research exception on the database right.18x European Union, Study on the Legal Framework of Text and Data Mining (TDM) (2014), at 51, available at: https://publications.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/074ddf78-01e9-4a1d-9895-65290705e2a5/language-en (last visited 1 July 2019). -

4 TDM as Mandatory Exception from Article 5(a) of Database Directive

Article 5 of the Database Directive, i.e. Directive 96/9/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 11 March 1996 on the legal protection of databases, OJ L 77 of 27 March 1996, 20, contains an exhaustive list of the exclusive rights vested in the author of a database subject to Article 2(b) that leaves without prejudice of the Rental and Lending Rights Directive the rights of rental and lending of a database under the provisions of Directive 2006/115/EC.

Article 5(a) of the Database Directive refers to the right of reproduction of the database. According to it:In respect of the expression of the database which is protectable by copyright, the author of a database shall have the exclusive right to carry out or to authorise:

temporary or permanent reproduction by any means and in any form, in whole or in part;

The right of reproduction of a database has a wide formulation in the sense that it covers any direct or indirect way of reproduction, complete or partial reproduction, and any permanent or temporary act of reproduction of a database in compliance with Article 9(1) of the Berne Convention. A transient form of reproduction is also included in the notion of the reproduction of a database of Article 5(a) of the Database Directive. The broad wording of ‘temporary’ and the fact that the obligatory exception of Article 6(1) of the same Directive takes into account the interests of the ‘lawful user’ of the database attest to the conclusion that the reproduction right of the database of Article 5(a) considers all forms and ways of reproduction, including the ‘transient’ reproduction.19x Walter and Lewinski, above n. 3, 9.5.7, 715-6; I. Stamatoudi, P. Torremans, EU Copyright Law – A Commentary (2014), 9.21, 313-4.

Therefore, in the case of TDM upon a database, even transient reproduction, in whole or in part, of the database is subject to the protectable copyright of the author of the database, who has the exclusive right to allow or forbid it.

Articles 3 and 4 of the new Directive on Copyright in the DSM mandatorily exclude the TDM executed upon a database in compliance with the requirements that the said provisions describe from the exclusivity power of the author of the database and the requirement of his or her prior written consent.

The mandatory exception of Articles 3 and 4 of the new Directive on Copyright in the DSM pertains to acts of TDM that may impact on the expression of the database that is protected by copyright, i.e. the selection or arrangement of the contents of the database. For any possible impact of TDM on unprotectable parts of the database’s structure, upon which there is no exclusive right of the author of a database, there is no provision in the Database Directive that could hamper the TDM.20x Walter and Lewinski, above n. 3, 9.5.4., at 715. -

5 TDM as Mandatory Exception from Article 7(1) of Database Directive

Article 7(1) of the Database Directive rules that:

1. Member States shall provide for a right for the maker of a database which shows that there has been qualitatively and/or quantitatively a substantial investment in either the obtaining, verification or presentation of the contents to prevent extraction and/or re-utilisation of the whole or of a substantial part, evaluated qualitatively and/or quantitatively, of the contents of that database.

TDM is set in Articles 3 and 4 of the new Directive on Copyright in the DSM as an exception to the rights provisioned in Article 7(1) of the Database Directive. This means that the maker of a database cannot claim his/her/its sui generis right with the aim of forbidding TDM activity. Also, it means that it is not necessary for the holder of the sui generis right to license the right extraction and/or reutilisation of the whole or of a substantial part of the database for the implementation of TDM. TDM may be implemented with or without the licence of the maker of a database for acts of extraction and/or reutilisation of the whole or of a substantial part of the database.

The holder of the sui generis right may be a natural person or a legal entity or a group of natural persons and/or legal entities such as partnerships or group of companies since the sui generis right is not an author’s right under the Continental European legal system.21x Ibid., 9.7.16., at 750. The maker of the database and the holder of the sui generis right is the person who/which took the initiative to make the protected database that is set under TDM activity and who/which bears the risk of investing for the aforesaid database (Directive 96/9/EC).22x See Recital 41 of the Database Directive according to which the maker of a database is the person who takes the initiative and the risk of investing; … this excludes subcontractors in particular from the definition of maker. A defining issue for naming the holder of the sui generis right is to spot the person/entity who/which made the substantial investment for the creation of a database.23x Stamatoudi and Torremans, above n. 19, 9.42, at 325.

TDM is set as a mandatory exception of Article 7(1) of the Database Directive regarding actions of extraction and/or reutilisation of the whole or of a substantial part, evaluated qualitatively and/or quantitatively, of the contents of a database. These actions may pertain to the whole database or a separate module of a database that by itself fulfils the conditions for protection of a database.

Extraction means removal and copying of contents of a database. Extraction includes translation of the database’s content. The meaning of ‘extraction’ is wide, covering at least the same acts covered by the term ‘reproduction’ under copyright and related rights.24x Walter and Lewinski, above n. 3, 9.7.25., at 754. Therefore, in a typical TDM activity in which the contents of a database are copied, turned into a machine-readable format compatible with the TDM technology and uploaded onto a platform, there is no doubt about the fact of extraction of the contents of a database through the TDM activity. Besides, TDM entails extraction of contents of a database since in almost all cases of TDM activity there is permanent transfer of the contents that are stored in a permanent manner in a medium other than the database for more than a limited period of time after extraction.25x See CJ Case C-545/07, Apis-Hristovich EOOD v. Lakorda AD, [2009] ECR I-1627, mn.55, available at: http://curia.europa.eu/juris/liste.jsf?num=C-545/07 (last visited 1 July 2019).

‘Reutilisation’ means all forms of making, directly or indirectly, a database available to the public.26x See CJ Case C-203/02, mn. 67. It covers both acts of exploitation and acts performed by users without the aim of obtaining proceeds from marketing the contents of a database.27x Walter and Lewinski, above n. 3, 9.7.35., at 758. -

6 TDM as Mandatory Exception from Article 2 of InfoSoc Directive

TDM is set in Articles 3 and 4 of the new Directive on Copyright in the DSM as an exception to the right provisioned in Article 2 of the InfoSoc Directive. Specifically:

Article 2 of the InfoSoc Directive refers to the reproduction right, which is at the core of copyright and related rights and is of eminent importance within the concept of copyright protection.28x Ibid., 11.2.1., at 963. Through the provisions of Articles 3 and 4 of the new Directive on Copyright in the DSM, TDM is set as a mandatory exception to the reproduction right in its broad meaning and extension including all categories of works. It includes, also, direct and indirect and permanent and temporary reproductions with the exception of the application of Article 5(1) of the InfoSoc Directive regarding temporary acts of reproduction that are transient and incidental and an integral and essential part of a technological process the sole purpose of which is to enable transmission in a network between third parties by an intermediary or a lawful use of a work or other subject matter, and that have no independent economic significance. It includes reproduction by any means and in any form, as well as reproduction of the whole work or parts of a work provided that the part concerned complies with the originality requirement.

The broad meaning of the reproduction right of Article 2 of the InfoSoc Directive is described in Recital 21 of the InfoSoc Directive, according to which a broad definition of the acts of reproduction is needed to ensure legal certainty within the internal market in the EU and has been confirmed by the CJ in the Infopaq case.29x See CJ Case C-5/08 (2009), Case C-5/08 Infopaq International A/S v. Danske Dagblades Forening, 2009 I-06569, available at: http://curia.europa.eu/juris/liste.jsf?num=C-5/08 (last visited 1 July 2019). The meaning of reproduction is to be determined technically rather than functionally.30x Walter and Lewinski, above n. 3, 11.2.17., at 968.

Therefore, reference to Article 2 of the InfoSoc Directive in the provisions of Articles 3 and 4 of Directive 2019/790/EU was necessary in consideration of the typical TDM operation, which includes reproduction of works by copying them in whole or in part with the aim of preprocessing them and turning them into machine-readable format compatible with the technology to be deployed for the TDM operation, as well as by uploading – depending on the TDM technology – the preprocessed materials on a platform for further extraction of data from works and recombination of the data for the identification of patterns into the final output. -

7 TDM in the Text of National Laws of a Few EU Members

7.1 UK

The UK legislature amended its Copyright law by S.I. 1992/3233, regulation 7, S.I. 1997/3032, regulation 8 and S.I. 2003/2498, regulation 9. Section 29A, which was added to the Copyright and Rights in Performances (Research, Education, Libraries and Archives) Regulations 2014, came into force on 1 June 2014. The amended Copyright law in the UK, which provides for TDM to the lawful user for the sole purpose of computational analysis for non-commercial research, but does not cover the reproduction of databases, provides as follows (emphasis added):31x See http://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2014/1372/regulation/3/made (last visited 1July 2019).

29A Copies for text and data analysis for non-commercial research

The making of a copy of a work by a person who has lawful access to the work does not infringe copyright in the work provided that –

the copy is made in order that a person who has lawful access to the work may carry out a computational analysis of anything recorded in the work for the sole purpose of research for a non-commercial purpose, and

the copy is accompanied by a sufficient acknowledgement (unless this would be impossible for reasons of practicality or otherwise).

Where a copy of a work has been made under this section, copyright in the work is infringed if –

the copy is transferred to any other person, except where the transfer is authorised by the copyright owner, or

the copy is used for any purpose other than that mentioned in subsection (1)(a), except where the use is authorised by the copyright owner.

If a copy made under this section is subsequently dealt with –

it is to be treated as an infringing copy for the purposes of that dealing, and

if that dealing infringes copyright, it is to be treated as an infringing copy for all subsequent purposes.

In subsection (3) “dealt with” means sold or let for hire, or offered or exposed for sale or hire.

To the extent that a term of a contract purports to prevent or restrict the making of a copy which, by virtue of this section, would not infringe copyright, that term is unenforceable.

Research and private study

1C. –

Fair dealing with a performance or a recording of a performance for the purposes of research for a non-commercial purpose does not infringe the rights conferred by this Chapter.

Fair dealing with a performance or recording of a performance for the purposes of private study does not infringe the rights conferred by this Chapter.

Copying of a recording by a person other than the researcher or student is not fair dealing if –

in the case of a librarian, or a person acting on behalf of a librarian, that person does anything which is not permitted under paragraph 6F (copying by librarians: single copies of published recordings), or

in any other case, the person doing the copying knows or has reason to believe that it will result in copies of substantially the same material being provided to more than one person at substantially the same time and for substantially the same purpose.

To the extent that a term of a contract purports to prevent or restrict the doing of any act which, by virtue of this paragraph, would not infringe any right conferred by this Chapter, that term is unenforceable.

Expressions used in this paragraph have the same meaning as in section 29.

Copies for text and data analysis for non-commercial research

1D. –

The making of a copy of a recording of a performance by a person who has lawful access to the recording does not infringe any rights conferred by this Chapter provided that the copy is made in order that a person who has lawful access to the recording may carry out a computational analysis of anything recorded in the recording for the sole purpose of research for a non-commercial purpose.

Where a copy of a recording has been made under this paragraph, the rights conferred by this Chapter are infringed if –

the copy is transferred to any other person, except where the transfer is authorised by the rights owner, or

the copy is used for any purpose other than that mentioned in sub-paragraph (1), except where the use is authorised by the rights owner.

If a copy of a recording made under this paragraph is subsequently dealt with –

it is to be treated as an illicit recording for the purposes of that dealing, and

if that dealing infringes any right conferred by this Chapter, it is to be treated as an illicit recording for all subsequent purposes.

To the extent that a term of a contract purports to prevent or restrict the making of a copy which, by virtue of this paragraph, would not infringe any right conferred by this Chapter, that term is unenforceable.

Expressions used in this paragraph have the same meaning as in section 29A.

7.2 FR

In France, the legislature of Law No. 2016-1231 for a Digital Republic (Loi pour une République numérique), introduced TDM exceptions both applying to works (art. L.122-5, 10 of the CPI) and databases (art. L.342-3, 5 of the CPI).32x Art. 38 of the Law No. 2016-1231 for a Digital Republic added paragraph 10 to art. L.122-5 and paragraph 5 to art. L.342-3 of the French Intellectual Property Code (Code de la Propriété Intellectuelle, CPI). French exceptions cover acts of reproduction from ‘lawful sources’ (materials lawfully made available with the consent of the rights holders) for TDM as well as storage and communication of files created in the course of TDM research activities.33x C. Geiger, G. Frosio, O. Bulayenko, The Exception for Text and Data Mining (TDM) in the Proposed Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market-Legal Aspects (2018), 17-8, available at: http://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/IDAN/2018/604941/IPOL_IDA(2018)604941_EN.pdf (last visited 1 July 2019).

The French ruling for TDM, Article 38 of the Law No.2016-1231 for a Digital Republic, has as follows:34x Unofficial translation. The original text in the French law provides as follows:

Art. 38

Le code de la propriété intellectuelle est ainsi modifié:

1° Après le second alinéa du 9° de l’article L. 122-5, il est inséré un 10° ainsi rédigé:

« 10° Les copies ou reproductions numériques réalisées à partir d’une source licite, en vue de l’exploration de textes et de données incluses ou associées aux écrits scientifiques pour les besoins de la recherche publique, à l’exclusion de toute finalité commerciale. Un décret fixe les conditions dans lesquelles l’exploration des textes et des données est mise en œuvre, ainsi que les modalités de conservation et de communication des fichiers produits au terme des activités de recherche pour lesquelles elles ont été produites ; ces fichiers constituent des données de la recherche ; »

2° Après le 4° de l’article L. 342-3, il est inséré un 5° ainsi rédigé:

« 5° Les copies ou reproductions numériques de la base réalisées par une personne qui y a licitement accès, en vue de fouilles de textes et de données incluses ou associées aux écrits scientifiques dans un cadre de recherche, à l’exclusion de toute finalité commerciale. La conservation et la communication des copies techniques issues des traitements, au terme des activités de recherche pour lesquelles elles ont été produites, sont assurées par des organismes désignés par décret. Les autres copies ou reproductions sont détruites. »

After the second paragraph of 9° of article L.122-5, a 10° is inserted as follows:10° Electronic copies or reproductions realised from a legal original, for the purpose of text and data mining included or associated in a scientific publication for the needs of the public research, excluding commercial exploitation. A decree lays down the conditions in which text and data mining are employed, as well as the modalities of preservation and communication of the files produced at the end of the research activities for which they have been produced; these files constitute research data;

After the 4° of the article L.342-3 is inserted a 5°, thus written:

5° Electronic copies or reproductions of a database realised by someone who has a legal access to it, for the purpose of text and data mining included or associated to scientific publications for the needs of a research activity, excluding commercial exploitation. The preservation and the communication of the technical copies made during the process, at the end of the research activities for which they have been produced, are provided by institutions appointed by decree. Other copies or reproductions are destroyed.

The French legislature opted to leave the ruling of the matter of the conditions under which TDM can be undertaken as well as the modalities for storing and communicating research files that were created for TDM purposes to an actualisation decree. TDM is restricted solely to text and data included in or associated with scientific writings. TDM is ruled only for non-commercial purposes; it cannot pursue commercial objectives and should be limited to the needs of (public) research.35x Geiger, Frosio, & Bulayenko, above n. 33, at 18.7.3 EE

The Estonian legislature amended the country’s Copyright Act of 1992 and, as of 1 January 2017, introduced TMD in paragraph 3 of Article 19 titled ‘Free use of works for scientific, educational, informational and judicial purposes’. The Estonian Copyright Act (emphasis added) makes the following provision:

The following is permitted without the authorisation of the author and without payment of remuneration if mention is made of the name of the author of the work, if it appears thereon, the name of the work and the source publication … 3) processing of an object of rights for the purposes of text and data mining and provided that such use does not have a commercial objective;

The Estonian Copyright Act (1992) already has a research exception (Section 19) applicable within the framework of language research. However, for the sake of legal clarity, it was considered relevant to add a specific exception for TDM. The UK approach is used as a benchmark. The exception provided in Estonian law is applicable for work and objects with related rights (such as performances).7.4 DE

Also, in 1 September 2017 Germany amended its Copyright law, and the amendment has come into force as of 1 March 2018, introducing TDM in Section 60d titled ‘Text and data mining’. According to this provision in German Copyright Act of 9 September 1965, as last amended by Article 1 of the Act of 1 September 2017 (emphasis added):

In order to enable the automatic analysis of large numbers of works (source material) for scientific research, it shall be permissible 1. to reproduce the source material, including automatically and systematically, in order to create, particularly by means of normalisation, structuring and categorisation, a corpus which can be analysed and 2. to make the corpus available to the public for a specifically limited circle of persons for their joint scientific research, as well as to individual third persons for the purpose of monitoring the quality of scientific research. In such cases, the user may only pursue non-commercial purposes.

If database works are used pursuant to subsection (1), this shall constitute normal use in accordance with section 55a, first sentence. If insubstantial parts of databases are used pursuant to subsection (1), this shall be deemed consistent with the normal utilisation of the database and with the legitimate interests of the producer of the database within the meaning of section 87b (1), second sentence, and section 87e.

Once the research work has been completed, the corpus and the reproductions of the source material shall be deleted; they may no longer be made available to the public. It shall, however, be permissible to transmit the corpus and the reproductions of the source material to the institutions referred to in sections 60e36x Section 60e refers to libraries, namely Publicly accessible libraries which neither directly nor indirectly serve commercial purposes (libraries). and 60f37x Section 60f refers to archives, museums and educational establishments. for the purpose of long-term storage.

The TDM exception in German law covers the acts of reproduction necessary for undertaking TDM and the acts of making available the corpus of materials produced by TDM activity (e.g. source materials that were normalised, structured and categorised) to a specifically limited circle of persons for their joint scientific research, as well as to individual third persons for the purpose of monitoring the quality of scientific research. Once the TDM project is completed, the ‘corpus’ can be sent to institutions designated by law for long-term storage. Any other copy made should be deleted.

-

8 Article 4(4)(b) of Greek Law 4452/2017 for TDM of NLG

A recent development in Greece’s legal framework on the National Library of Greece (NLG) stipulates activities that are within the TDM operation. Specifically, law 4452/2017, which is titled ‘Regulation on State Language Certificate subject matter, on the National Library of Greece and on other provisions’, includes in its text the provision of Article 4(4)(b), according to which the NLG operates as the official National Depository and Archive of digital publications, data and metadata produced in the country or related to Greek culture. This operation includes the monitoring and archiving of the Internet (Web archiving) or other technology environment. To this end, the NLG shall undertake, allocate and coordinate the actions concerned at the national level.

This provision of Article 4(4)(b) of law 4452/2017 is the first in the Greek legal system that caters for TDM activities. The provision is too general, probably vague, and not proper in its wording. However, the analysis in this text does not aim at elaborating on the bad phrasing or vagueness in the provision of Article 4(4)(b) of law 4452/2017.

Article 4(4)(b) of law 4452/2017 sets the TDM activity in Greece under the responsibility of the NLG, which is named as the organisation to undertake, allocate and coordinate action of text and data analysis at the national level. The ‘monitoring’ of the Web is meant to be the Web harvesting activity; the archiving of the Internet is meant to be the archiving of works harvested from the Internet. Thus, the NLG is ruled to be the proper organisation for running and overseeing TDM activity in Greece. Other organisations may deploy TDM activities under the coordination of the NLG, which is the national depository and archive of works on the Internet, including data and metadata produced in Greece or related to the Greek culture.

Article 4(4)(b) of law 4452/2017 preceded any EU regulation on TDM. The proposal for a Directive on Copyright in the DSM was not part of the ‘acquis communautaire’ when the Hellenic Parliament passed law 4452/2017. -

9 Tinkering with TDM in NLG

As noted previously, the NLG is described in Article 4(4)(b) of law 4452/2017 as the official national depository and archive of digital publications, data and metadata produced in the country or that is related to Greek culture. NLG’s operation includes – among other legally founded statutory goals – the monitoring and archiving of the Internet (Web archiving) or other technology environment. To this end, NLG shall undertake, allocate and coordinate the actions concerned at the national level. There is no other provision for TDM in the Greek legal framework to date. Actually, the provision of Article 4(4)(b) of law 4452/2017 is not a provision that sets an exception or limitation to copyright for TDM and for scientific or other purposes, but rather one that describes NLG’s prime role in TDM activity, limited to the sense of Web archiving, in Greece.

Regarding TDM, the paradox in the ruling of law 4452/2017 is obvious: the Greek legislature rules upon the key TDM player in the Greek market despite the fact that it has yet to rule upon the TDM game! That said, and with all due respect for the Greek legislature, this is by no means the sole paradox one can find in the national legal system.

Once the provision of Article 4(4)(b) of law 4452/2017 became effective, NLG made its first attempts with TDM. The first attempts of NLG with TDM were supported technically by the Research Team of Data & Web Mining (DB-net)38x See DB-net, a.k.a. the Research Team of Data & Web Mining, Athens University of Economics and Business, available at: http://www.db-net.aueb.gr (last visited 1 July 2019). of Athens University of Economics and Business. Leveraging on the technical expertise of DB-net, NLG has tinkered with TDM repeatedly, so far.

On February 2017 NLG deployed TDM for the first time, targeting Greek websites at the national level. This first attempt was a broad crawling of the Web for websites under the .gr domain or websites under the .edu or .com domains that were composed in Greek. By that time – and even currently – NLG was aware of the fact that the Greek legal system does not leave any room for consideration of making the output of TDM available to the public. The first NLG’s attempt with TDM – and actually all subsequent ones – were made for scientific purposes, more precisely for the purpose of extracting new knowledge from statistical information coming out of the TDM process upon the works submitted to it, as well as for purposes related to NLG’s statutory goals such as the purpose of saving and preserving Greek Web archives as part of Greece’s national cultural heritage.

Before NLG’s first TDM activity, the DB-net research team had tested its TDM know-how by deploying TDM activity targeting the websites of Athens University of Economics and Business (AUEB).39x A detailed announcement of the first Web archiving attempt in Greece by AUEB was presented during the 19th Pan-Hellenic Conference of Academic Libraries in 2010 in Athens. See V. Plachouras, C. Kapetis, M. Vazirgiannis, Archiving the Web Sites of Athens University of Economics and Business (2010), Athens, available at: http://www.db-net.aueb.gr/files/ArchivingAUEB_CameraReady_V6.pdf (last visited 1 July 2019). Experimental TDM activity targeting Greek websites deployed by the DB-net research team had also preceded NLG’s tinkering with TDM.40x See C. Lampos, M. Eirinaki, D. Jevtuchova, M. Vazirgiannis, Archiving the Greek Web (n/a), available at: http://www.db-net.aueb.gr/files/LEJV04-IWAW.pdf (last visited 1 July 2019); S. Paulakis, C. Lampos, M. Eirinaki, M. Vazirgiannis, SEWeP: A Web Mining System Supporting Semantic Personalization (n/a), available at: http://www.db-net.aueb.gr/files/PLEV04-PKDD.pdf (last visited 1 July 2019). The DB-net research team of AUEB had cross-tested TDM technology upon Greek websites starting from February 2010 and repeatedly at least four times until May 2010.

As of February 2017, NLG has deployed two broad TDM activities on the Greek Web.41x The information about TDM deployed by NLG by the authors of this article straight from the NLG. NLG scientists made a public announcement upon NLG’s first two efforts to archive the Greek Web during the proceedings of the 24th Pan-Hellenic Conference of Academic Libraries that took place on November 1-2, 2018, in Larissa, Greece; D. Chios, M. Vazirgiannis, P. Meladianos, G. Angelakis, Archiving the Greek Web (2018). The first Web harvesting was deployed with an interest in mining and archiving only text data from websites on top level .gr national domain in Greek or other languages or from other websites that used Greek and were for this reason considered Greek sites. Websites composed in Greek under the .edu and .com domains were harvested too.

Websites allowing authorised access to their content were not targeted during NLG’s Web harvesting. NLG’s TDM activity excluded, also, websites using the Robots Exclusion Protocol42x For the meaning of Robots Exclusion Protocol see http://www.robotstxt.org/orig.html (last visited 1 July 2019). (included .txt files) or those considered as media resources.

In order to delimit the Greek sites, as a target group of the first mining, extensive research through Web search engines and through thematic portals related to Greek websites was conducted. The volume of the first broad crawling of the Greek Web was an archiving amounting to 18 TB of information.

The stages of the first implementations of TDM in Greece by NLG are presented in Table 1.Table 1 Working Stages of Web Archiving in Greece by NLGStage I Economic and technical study on the needs and content of the Greek Web harvest. Study of international experience 1st Web harvest:

broad crawl – national level:

text data only

Stage II Definition of ‘Greek’ sites to be mined Stage III Data Analysis of 1st Web harvest to create a National Web Archiving System Stage IV Installing and checking the operation of tools for all phases of national Web archiving: extraction, archiving/classification and, finally, user search and access: Heritrix for harvesting, Solr for indexing and Open Wayback for website reconstitution. Use of Netarchive Suite. 2nd Web harvest:

broad – national level:

text only

thematic (text and images)

Stage V Developing a National Archiving System of Greek Web (‘EΣΑΕΙ’): the Greek user interface/librarian During the second deployment of TDM activity for archiving the Greek Web, the first mining of selective content took place in consideration of the following themes:

Local government,

News and

Education (schools, universities, etc. Mainly edu.gr, sch.gr and mysch.gr.)

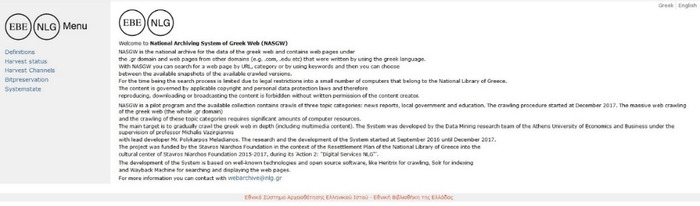

The National Archiving System of Greek Web (‘ΕΣΑΕΙ’ National System)43x Greek logo of the System (“EΣΑΕΙ”) connotes the ancient Greek language, specifically the phrase (εσαεί < ἐςἀεί), which means ‘forever’. has a user interface in the Greek and English languages and search tools to archive from the Greek Web archiving process and TDM procedure.

The National Archiving System of Greek Web user interface

In this ΕΣΑΕΙ’ National System the act of website-searching refers to selective-thematic harvesting, and the user searches by keyword, URL name and thematic category name.

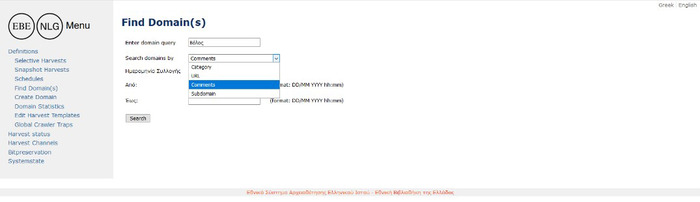

Search tools of The National Archiving System of Greek Web

The aforesaid system also offers the option of using a time frame selection tool in combination with keyword and domain-search tools.

Search tools of The National Archiving System of Greek Web

The system has not become available to any third party, whether researcher or not, except the NLG. Until today the sole user has been the NLG librarian since, as already mentioned, there is still no proper legal framework to facilitate the making available to the public of the harvested and archived content from the Web to the research community owing to legal restrictions for intellectual property protection according to Greek legislation.

NLG has set specific goals to improve the ‘ΕΣΑΕΙ’ National System and evolve TDM and Web archiving in the near future. Specifically, it aims to improve the categorisation of websites in order to make it possible to implement selective Web harvesting into new categories in the foreseeable future. In addition, NLG intends to improve accessibility tools, as well as to focus on partnership development regarding TDM in Greece. NLG is already a member of the International Internet Preservation Consortium (IIPC),44x See about IIPC at: https://netpreserveblog.wordpress.com/2018/05/22/iipc-content-development-group-whats-on-in-2018 (last visited 1 July 2019). which lists as members the EU Member States’ National Libraries and other international entities for the purpose of preservation of the World (Cultural) Heritage that ‘lives’ on the Web.

The task of crawling the Web and retrieving from its content works relating to the Greek culture and Greeks has been vested with NLG through the provision of Article 4(4)(b) of law 4452/2017. This is a difficult task that, aside from the proper legal framework – which does not exist, currently – requires collaboration at the national and international levels such as partnership between NLG and the Internet Archive.

Regarding the possibilities for researchers to delve into the collection of works that form the output of NLG’s TDM activity, the sky is the limit. NLG has expressed strong interest in researching the TDM output on scientific purposes related to the Greek language itself, and as a means of inferring from such output ideas with a global resonance over time. The development of any kind of language tools (huge dictionaries, word roots, embedded words etc.) that preserve and highlight the Greek language as a communication medium and as a transmitter of spirit and culture is one of NLG objectives. These language tools will also help in the association and identification of websites based on the semantic relevance of Greek words. In addition, Greek language tools could help in user-communities’ identification. Researchers who can benefit from research on collections that originate from Web harvesting and TDM functions could include linguists, historians, journalists, sociologists and other scientists.

One of the issues intended to be subject to thematic Web harvesting by NLG pertains to websites and data related to Greek emigrant Hellenism. This intention demonstrates cultural values, particularly major national particularities and needs as well as the essential concept of ‘nation’ and the Greek national heritage. -

10 TDM and Digital Legal Deposit

TDM and legal deposit as technological and administrative processes, respectively, are not in sync, currently. The legal deposit is an administrative process in which the publishers or authors submit one or more copies of each of their publications for specific deposit with the aim of preserving the written cultural heritage or the cultural heritage that has been imprinted on some medium. Where the deposit of copies of works is provided by law, a legal deposit is made and may be described in law either as compulsory or as voluntary. Compulsory legal deposit is provisioned as mandatory in law, while in the case of voluntary legal deposit the law rules that legal deposit is left to voluntary agreements between the institution to which the deposit is made and publishers or authors who ought to proceed to legal deposit of their works. In most cases of legal deposit, the national library of the country where the law applies is defined as the institution to which the works must or ought to be deposited. Alternative deposit areas and other libraries, such as parliamentary, academic, public, community libraries as well as public archives, may, however, be envisaged in legal deposit provisions.

The statutory legal deposit in Greece was provisioned for the first time through law ΣΜΗ/1867, which was amended by law ΓΧΛΖ#/1910.45x See law ΓΧΛΖ#/1910 amending the provisions of law ΣΜΗ# regarding the National Library of Greece and applying to the Library of the Parliament of Greece, including provisions for public and private libraries, Themis 1910. Both laws ruled the compulsory legal deposit in which each work had to be deposited in the NLG in two copies as well as in the Library of the Parliament of Greece in one copy. These laws were amended by law 2557/1997. In 2003, law 2557/1997 was amended by law 3149/2003, which ruled on subject matter for the NLG. Regarding the legal deposit of works in the NLG, the provisions of Article 12(7), (9), (10) & (12) of law 3149/2003 are important.

The World Intellectual Property Organization provides information on the legislation for administrative systems for legal deposit in effect, worldwide.46x WIPO, Summary of the Responses to the Questionnaire for Survey on Copyright Registration and Deposit Systems, Annex B.1, available at: http://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/copyright/en/registration/pdf/b1_legislation_countries.pdf (last visited 1 July 2019). There are both compulsory and voluntary legal deposit systems; there are both hard copy (traditional) and electronic legal deposit systems.

WIPO information on the legal deposit systems worldwide indicates that:

The majority of countries with a legal deposit system in effect have ruled upon it through statutes for copyright.47x These countries are the following: Albania, Algeria, Armenia, Argentina, Austria, Bahrain, Republic of Belarus, Belize, Bhutan, Brazil, Burundi, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Ecuador, Finland, Ghana, Greece, Guatemala, Guinea, Hungary, Ireland, Jamaica, Japan, Italy, Kenya, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, Republic of Korea, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxemburg, Madagascar, Mali, México, Republic of Moldova, Mongolia, Monaco, Montenegro, Namibia, Nepal, New Zealand, Norway, Oman, Pakistan, Peru, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Thailand, Tunisia, Ukraine, United Kingdom and United States of America.

The majority of countries with a legal deposit system in effect have opted for compulsory legal deposit.48x The following countries have compulsory legal deposit: Albania, Algeria, Argentina, Austria, Bahrain, Belize, Brazil, Bhutan, Chile, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Finland, Greece, Guatemala, Hungary, Kenya, Republic of Korea, Ireland, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxemburg, Madagascar, Mexico, Republic of Moldova, Monaco, Montenegro, Namibia, New Zealand, Norway, Pakistan, Peru, Romania, Russian Federation, Saudi Arabia, Serbia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Sweden, Thailand, Trinidad & Tobago, Ukraine, United Kingdom and United States of America.

Voluntary legal deposit is an exception to the rule, and few countries have adopted it.49x The following countries have voluntary legal deposit systems: Armenia, Burundi, Guinea, Mali, Mongolia and Oman.

In almost all cases of legal deposit systems the aim is 1) proof of publication of the deposited work, 2) the production of statistical information regarding the published works, as well as bibliographical information regarding the cultural heritage of works published in the country, 3) meeting the needs for scientific research through the pool of deposited works and 4) cultural preservation and development of libraries and archiving organisations.

There are countries in which the legal deposit system is not related to or is part of the copyright legal framework of the country.50x The countries in which the national legal deposit system is not part of the copyright law legal framework are the following: Belize, Republic of Belarus, Bhutan, Brazil, Burundi, Colombia, China, Costa Rica, Croatia, Czech Republic, Hungary, Ireland, Jamaica, Japan, Kenya, Republic of Korea, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Mali, México, Republic of Moldova, Mongolia, Namibia, Nepal, New Zealand, Peru, Serbia, Spain, Thailand, Trinidad & Tobago and the United States of America.

The legal deposit systems cater for works of culture in print or in electronic – digital – format. There are countries in which the legal deposit legislation describes indicatively what is subject to legal deposit. This description may include 1) print materials and materials in electronic format (government publications, collections of laws, collection of international agreements, banknotes, securities, booklets, flyers, posters, postcards, official and trade forms, maps, atlases, scores, text, notes, maps, special prints, journals, newspapers, magazines, bulletins, geographical and other charts, etc.); 2) materials for the blind or partially sighted; 3) special materials for physically impaired persons, including Braille materials; 4) official documents; 5) software or computer programs; 6) musical works in notation and recorded; 7) audio-visual works/performances, broadcast materials, phonogram; 8) electronic editions; 9) non-published documents; 10) patent documents; 11) databases; 12) standards; 13) coins; 14) combined documents.

There are countries that do not exclude any work from the legal deposit system.51x These are the following countries: Argentina, Armenia, Bahrain, Belize, Bhutan, Brazil, Burundi, China, Colombia, Costa Rica, Czech Republic, Ecuador, Hungary, Jamaica, Liechtenstein, Luxemburg, Mali, México, Montenegro, Mongolia, Pakistan, Peru, South Africa, Spain, Sri Lanka, Trinidad & Tobago and Ukraine.

In most countries in which the law caters for both the legal deposit of hard copies and the digital legal deposit copies in electronic format/means, the law does not differentiate substantially regarding the obligation and the consequences of not abiding by it for the legal deposit. Very few countries have passed laws regarding the digital legal deposit in the sense of harvesting of works from the Web.

Systems for the legal deposit differ significantly in regard to the number of copies of a work that is required by law to be deposited. Differentiation applies also to the time frame within which a work must be compulsorily deposited.52x Regarding the requirement for the number of copies of a work for legal deposit, as well as the time frame in which the legal deposit must happen, see WIPO, Annex B.2. table, available at: http://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/copyright/en/registration/pdf/b2_number_of_copies_required.pdf (last visited 1 July 2019).

Responsible entities for the operation of the legal deposit are the national libraries; there are countries in which the responsibility for the legal deposit is assigned to legal entities other than the national libraries.53x Regarding the legal entities responsible for the operation of the legal deposit, see WIPO, Annex B.3. table, available at: https://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/copyright/en/registration/pdf/b3_deposit_entities_details.pdf (last visited 1 July 2019).

Accessibility to works collected through the legal deposit system is free of charge.54x Countries in which works collected through the legal deposit system are made available free of charge are the following: Albania, Argentina, Austria, Bahrain, Republic of Belarus, Belize, Brazil, Burundi, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Ecuador, Finland, Ghana, Greece, Guinea, Hungary, Ireland, Jamaica, Japan, Italy, Kenya, Republic of Korea, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxemburg, Madagascar, México, Republic of Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Namibia, Nepal, New Zealand, Norway, Pakistan, Peru, Russia, Serbia, Singapore, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Thailand, Ukraine, United Kingdom and the United States of America.

In many countries the legal deposit system is linked to the assignment of the International Standard Books Number (ISBN) or the International Standard Serial Number (ISSN) or other such.55x See WIPO, Annex B.4, available at: https://www.wipo.int/export/sites/www/copyright/en/registration/pdf/b4_deposit_and_isbn_numbers.pdf (last visited 1 July 2019) regarding the linking of the legal deposit with ISBN or ISSN or other such numbering.

In consideration of legislation per legal deposit systems listed by WIPO, and especially regarding legal deposit systems of EU Member countries, the following conclusions can be drawn:

The main purpose of the legal deposit system in each EU Member country is to facilitate the long preservation of works and to ensure that there is unhindered access to the deposited works as part of the cultural heritage of each country.

The legal deposit systems in each EU Member State allow for the achievement of secondary goals such as updating national bibliographic information in consideration of cultural production of works deposited accordingly.

In all EU Member countries, legal deposit is understood as a process for adding one or more copies of each deposited work in a national archive maintained, in most cases, by the National Library of the country and/or by academic libraries or archiving institutions provisioned in law.

The legal deposit system may describe the process for depositing a hard copy of a work as well as for depositing a digital copy of a work online or offline.

The legal deposit system concerns the deposition of a work embedded either in a hard copy or in a digital means featuring the work. In the second case there is the ‘digital legal deposit’, which includes the process for deposition of a work online as well as the process for deposition of a digital copy of a work offline.

The default legal deposit system may favour either the compulsory or the voluntary option. In most cases of EU Member countries, the option of compulsory legal deposit prevails as the default.

Most EU Member countries have set legislation for the legal deposit of a number of non-digital copies of a work (hard copies). Though there are indications of interest in also setting up a process for the deposit of digital copies of a work, most EU Member countries have yet to finalise their digital legal deposit systems to the point where such a process can smoothly cater for both the legal deposit of a work imprinted in a digital means (CD-Rom, DVD etc.) and the online legal deposit of a work harvested from the Web.

Among the EU Member countries very few have developed fully functional legal deposit systems that can cater for e-books, e-journals and e-magazines, i.e. works published and marketed online. Furthermore, very few countries have designed and implemented Web harvesting systems in sync with legal deposit systems.

The ‘digital legal deposit’ of a work imprinted in digital means – it is also called ‘electronic legal deposit’ – pertains to the deposition of a work online through a process that may be linked with Web harvesting and Web archiving, too; it may also pertain to the electronic deposit of a work furnished in digital storage means. During the 1996 International Conference of Directors of National Libraries56x Conference of Directors of National Libraries, available at: http://www.cdnl.info/ (last visited 1 July 2019). a common statement of the participants was issued regarding the electronic legal deposit. In 1998, the Council of Europe and the ELBIDA – European Bureau of Library, Information, and Documentation Associations57x ELBIDA, available at: http://www.eblida.org/ (last visited 1 July 2019). – issued guidelines on regulation of a policy and the legal framework for libraries in Europe regarding – among other issues – the electronic legal deposit. In 2012, ELBIDA published a document describing the organisation’s basic principles on the acquisition of and access to e-books in consideration of the balanced interests of all the involved parties, specifically the rights holders and the users of works.58x ELBIDA, Basic Principles for the Acquisition of and Access to E-books (2012), available at: http://www.eblida.org/Special%20Events/Key-principles-acquistion-eBooks-November2012/GR-EBLIDA_Key_Principles_on_the_acquisition_of_and_access_to_E-books_by_libraries.pdf (last visited 1 July 2019). ELBIDA’s text on the basic principles for the acquisition of and access to e-books considered the 1981 UNESCO guidelines on the legal deposit, a text that was amended in 2000.59x UNESCO, Guidelines for Legal Deposit Legislation, available at: http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0012/001214/121413eo.pdf (last visited 1 July 2019).

Among the EU Member countries’ systems for digital legal deposit,60x For the legal deposit legislation of EU Member see for Austria, legislation available at: https://www.ris.bka.gv.at/Dokumente/BgblAuth/BGBLA_2009_I_8/BGBLA_2009_I_8.pdfsig (last visited 1 July 2019); for Croatia, legislation available at: https://narodne-novine.nn.hr/clanci/sluzbeni/1997_10_105_1616.html (last visited 1 July 2019); for Denmark, legislation available at: http://www.kb.dk/en/kb/service/pligtaflevering-ISSN/lov.html (last visited 1 July 2019); for Estonia, legislation available at: https://www.riigiteataja.ee/akt/13315265?leiaKehtiv (last visited 1 July 2019); for Finland, legislation available at: http://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/alkup/2007/20071433 (last visited 1 July 2019); for Slovenia, legislation available at: https://www.uradni-list.si/glasilo-uradni-list-rs/vsebina?urlid=200669&stevilka=2977 (last visited 1 July 2019); for Spain, legislation available at: http://www.bne.es/opencms/es/Colecciones/Adquisiciones/DepositoLegal/docs/LEY_DL.pdf & URL: https://www.boe.es/buscar/act.php?id=BOE-A-2015-8338 & URL: https://www.boe.es/boe/dias/2015/07/25/pdfs/BOE-A-2015-8338.pdf (last visited 1 July 2019); for Germany, legislation available at: http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/pflav/index.html (last visited 1 July 2019); for the United Kingdom, legislation available at: http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2003/28/contents (last visited 1 July 2019); for Ireland, legislation available at: http://www.irishstatutebook.ie/eli/2000/act/28/enacted/en/html (last visited 1 July 2019). the most noticeable cases are those of Germany, The Netherlands, the United Kingdom and France.10.1 DE

In Germany, the law of 22 June 2006 per National Library of Germany – Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG)61x See unofficial translation in English of German law per National Library of Germany–Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG), available at: http://www.dnb.de/SharedDocs/Downloads/EN/DNB/wir/dnbg.pdf?__blob=publicationFile (last visited 1 July 2019). (i.e. the German National Library Act)62x See Gesetz über die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek [DNBG] [Act on the German National Library] (2006), BGBl. I, at 1338, as amended, available at: http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/dnbg/DNBG.pdf (last visited 1 July 2019). – rules the compulsory legal deposit of works in paragraph 14 (mandatory deposit requirement) for works imprinted in any digital means (e-books, e-journals, music -files, website content).63x See J. Gesley, Digital Legal Deposit: Germany (2018), Library of Congress, available at: https://www.loc.gov/law/help/digital-legal-deposit/germany.php (last visited 1 July 2019) for extensive description of the Digital Legal Deposit in the German National Library. The obligation for legal deposit pertains to works distributed in any material form, i.e. paper, electronic data storage media and other media, as well as to works distributed in immaterial forms, i.e. works distributed in public networks.64x See paragraph 3 of the German law regarding the National Library of Germany—Deutsche Nationalbibliothek (DNBG).

The German National Library Act requires the German National Library to collect, archive and catalogue all ‘media works’ (Medienwerke) published in Germany, all media works published abroad in the German language, all translations of German works published abroad, media works about Germany published abroad in other languages (Germanica), and printed works written or published between 1933 and 1945 by German-speaking emigrants. ‘Media works’ are defined as ‘all representations in text, image, and sound that are distributed in material form or made accessible to the public in immaterial form’. This includes non-commercial publications. ‘Printed publications’ (media works in material form) are defined as ‘all representations on paper, electronic data storage media, and other media’. ‘Online publications’ (media works in immaterial form) are defined as ‘all representations in public networks’. The collection mandate of the Library is further defined in the Legal Deposit Regulation (Pflichtablieferungsverordnung) and the Collection Guidelines (Sammelrichtlinien).65x See Verordnung über die Pflichtablieferung von Medienwerken an die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek [Pflichtablieferungsverordnung] [PflAV] [Legal Deposit Regulation], 17 October 2008, BGBl. I, at 2013, as amended, available at: http://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/pflav/PflAV.pdf (last visited 1 July 2019). Publications that are of no public interest may be exempted from the legal deposit programme.66x See Legal Deposit Regulation, § 1, para. 1, sentence 2. The legal deposit requirements support the mission of the German National Library to collect, archive and catalogue all such media works.

Although not explicitly stated in the Act, the German National Library’s collection mandate also covers the collection of websites.67x Collection Guidelines, para. 2.2.0.3.2; Deutscher Bundestag: Drucksachen und Protokolle [BT-Drs.] 16/322, 12-3. Unlike other national libraries in Europe, the German National Library did not begin collecting online publications by Web harvesting, but initially focused only on digital versions of existing physical publications. It started with monographs (e-books) and university publications (such as online doctoral dissertations) and eventually expanded to include other online publications such as e-papers and e-serials.

In 2010, the German National Library started making preparations for Web harvesting with the first Web crawl taking place in 2012. It collects only selected websites whose preservation is in the public interest in selective harvesting runs. Online publications in the public interest may include news websites, but also forums and blogs. However, as such websites are subject to constant change, the harvesting is repeated on a regular basis. The harvesting itself is automated, whereas the address of the website, collection depth and frequency are determined on a case-by-case basis and entered manually. The German National Library uses a ‘Web crawler’ that searches and stores predefined addresses for that purpose.68x Collection Guidelines, para. 2.2.0.3.2.

Web crawling is assumed to fall under the Library’s collection mandate. However, until an amendment of copyright law entered into force on 1 March 2018, the periodic harvesting of all German Internet domains, meaning all ‘.de’ domains, was prohibited. The German Copyright Act originally only allowed the German National Library to save online publications on a first and one-time basis. Repeated retrieval of an online publication was an extension of existing archival contents and therefore a violation of German copyright law.69x Copyright Act of 9 September 1965 (Federal Law Gazette I, at 1273), as last amended by Art. 1 of the Act of 1 September 2017 (Federal Law Gazette I, at 3346), available at: https://www.gesetze-im-internet.de/englisch_urhg/englisch_urhg.html (last visited 1 July 2019). In 2017, the legislature therefore proposed an amendment to the Copyright Act and the German National Library Act to grant the German National Library the right to automatically and repeatedly harvest works that fall under its collection mandate.70x Gesetz zur Angleichung des Urheberrechts an die aktuellen Erfordernisse der Wissensgesellschaft [Urheberrechts-Wissensgesellschafts-Gesetz] [UrhWissG] [Act to Align Copyright Law with Current Requirements of the Knowledge Society] [Copyright-Knowledge Society Act], 1 September 2017, BGBl. I, at 3346, available at: http://www.bgbl.de/xaver/bgbl/start.xav?startbk=Bundesanzeiger_BGBl&jumpTo=bgbl117s3346.pdf (last visited 1 July 2019). The Library is now entitled to archive websites even without requesting permission from the respective rights holders.71x German National Library Act, §16a, para. 1 (‘automatically and systematically’); Copyright Act, § 60e, para. 1.10.2 NL