-

1 Cartography, Colonialism and Indigenous Claims

Jean Beaudrillard famously declared that the map precedes and engenders the territory, reversing the supposition that territories simply exist and that maps map them.11xJ. Baudrillard, Simulacra and Simulations (Michigan: University of Michigan Press) (1997), at 1. In the great land grab undertaken by the colonial powers of Europe in modern and pre-modern eras, lands were claimed on paper before they were ever occupied.12xHarley, above n. 1, at 57. The Euclidian planes of the map of the world allowed Pope Alexander Paul, in the late 15th century, to notionally – and legally – partition ‘infidel lands’ in South America for distribution between rivals Portugal and Spain at the stroke of a pen;13xR. Williams, The American Indian in Western Legal Thought: The Discourses of Conquest (New York: Oxford University Press) (1990), at 80; P. Steinberg, ‘Lines of Division, Lines of Connection: Stewardship in the World Ocean’, 89 Geographical Review 254 (1999), at 255-8. the map’s visually blank spaces helped make it possible to imagine ‘undiscovered’ lands as unoccupied or empty terrae nullius;14xP. Carter, The Road to Botany Bay: An Exploration of Landscape and History (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press) (1987), S. Ryan, The Cartographic Eye: How Explorers Saw Australia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) (1996). and latitude and longitude allow even unknown places to be given a fixed position relative to Greenwich, England, the heart of a colonial empire, and made commensurate with other places on a universal grid. Maps necessarily distort reality in order to be practicable – through scale, projection, symbolism, cut-off and selection – but in doing so, they constitute territories in specific ways.15xThese cartographic ‘white lies’ are now well-known in critical geography: see Monmonier, above n. 7.

The advent of the bureaucratic modern state consolidated the tendency of records and artefacts to substitute for the real because of the roles they play in centralised decision-making. Maps have been a crucial material technology and practice both of jurisdiction and of property.16xS. Dorsett and S. McVeigh, Jurisdiction (Abingdon: Routledge) (2012), at 63; R. Kain and E. Baigent, The Cadastral Map in the Service of the State: A History of Property Mapping (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) (1992). As mentioned, it was the competing colonial claims to exclusive jurisdiction in overseas territories – particularly in relation to trade monopolies – that saw the first robust political mobilisation of maps.17xJ. Branch, The Cartographic State: Maps, Territory, and the Origins of Sovereignty (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) (2013); M. Biggs, ‘Putting the State on the Map: Cartography, Territory, and European State Formation’, 41 CSSH 374 (1999). Domestically, they also became an instrument for managing the affairs of government: the map renders the land legible through its reduction of the world to boundaries and surface areas, profitable tree species or types of land use, recording only what the state deems valuable. This stripped back frame of reference in turn permits greater forms of control. As James Scott notes of 19th-century forestry regimes in Europe, legible forests – those inventoried for saleable wood for the purposes of fiscal projection, for example – led to the next step of producing ‘simplified’ forests that were more profitable and easier to assess.18xJ. Scott, Seeing Like a State: How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed (New Haven: Yale University Press) (1999), at 18. The law of property, as another example, has been affected by a gradual process of ‘dephysicalisation’19xK. Vandevelde, ‘The New Property of the Nineteenth Century: The Development of the Modern Concept of Property’, 29 Buffalo Law Review 325 (1980). wherein what happens on the ground barely has an impact on the state of legal rights; in land title systems such as the Torrens system, what is on the face of the register is guaranteed to constitute the rights over any given parcel of land. The registered cadastral map is the property.20xA. Pottage, ‘The Measure of Land’, 57 Modern Law Review 361 (1994). Thus, aspects of social life are noticed, managed and produced through bureaucratic technologies and measurement.

The constitutive power of maps is particularly marked in the history of colonisation, and their role in it has been well documented in the literature.21xB. Harley, ‘Rereading the Maps of the Columbian Encounter’, 82 Annals of the Association of American Geographers 522 (1992); S. Banner, How the Indians Lost Their Land: Law and Power on the Frontier (Cambridge: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press) (2005); K. Brealey, ‘“Mapping Them Out”: Euro-Canadian Cartography and the Appropriation of the Nuxalk and Ts’ilhqot’in First Nations Territories, 1793-1916’, 39 Canadian Association of Geographers 140 (1995); G. Byrnes, Boundary Markers: Land Surveying and the Colonisation of New Zealand (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books) (2001); T.B. Mar, ‘Carving Wilderness: Queensland’s National Parks and the Unsettling of Emptied Lands, 1890–1910’, in T.B. Mar and P. Edmonds (eds.), Making Settler Colonial Space: Perspectives on Race, Place and Identity (Basingstoke: Palgrave) (2010); J.R. Miller, Skyscrapers Hide the Heavens: A History of Indian-White Relations in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press) (2000), at 125-47. Colonial officials enacted the powerful mythology of empty land by moving Indigenous peoples off their hunting territories and onto limited reserves. Land surveys shaped decision-making by treaty commissioners and other administrators as to the size and placement of reserves. As Cole Harris notes in the case of British Columbia, the ubiquitous maps ‘enabled the commissioners to locate their decisions in abstract geometrical space devoid of content except that which their own data collections and predilections inclined them to place there. They provided a measurable, transportable and archivable record, the minimalism of which tended to undermine Native claims.’22xC. Harris, Making Native Space: Colonialism, Reserves and Resistance in British Columbia (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press) (2002), at 235. Of course, colonialism was not simply effected through forms of representation, and the dispossession of Indigenous peoples took place at the sharp end of a whole machinery of colonial power – weapons, warships, troops23xC. Harris, ‘How Did Colonialism Dispossess? Comments from an Edge of Empire’, 94 Annals of the Association of American Geographers 165, at 166-7 (2004). and the more indirect but equally devastating diseases and decimation of big game like bison.24xJ.R. Miller, Compact, Contract, Covenant: Aboriginal Treaty-making in Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press) (2009), at 124, 150. Nevertheless, maps played a key role in these ‘theatres of power’.25xHarris, above n. 22, at 231. In the itinerant 19th- and early-20th-century treaty and land commissions, maps were part of formidable ritual display: red-coated police,26xMiller, above n. 24, at 159. commissioners in suits behind tables, documents bearing seals in front of them and all kinds of maps.27xHarris, above n. 22, at 231. More than being purely symbolic, maps were also an efficacious technology. They allowed officials and civilians alike to navigate spaces that were new to them, to use the information to control territory and to distribute land to settlers through provincial titling systems;28xS. Hornsby and H. Stege, Surveyors of Empire: Samuel Holland, JFW Des Barres and the Making of the Atlantic Neptune (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press) (2011). ‘they enabled a bureaucracy, essentially without local knowledge, to make decisions about localities.’29xHarris, above n. 23, at 176.

Out of necessity, Indigenous peoples also relied on European-made maps to resist colonial assumptions of ownership of their territories or claim land – for example when negotiating the size and placement of reserve lands,30xBrealey, above n. 21, at 153. or to monitor the implementation of treaties.31xIn 1884, for example, Treaty 6 chiefs from Saskatchewan demanded that the Minister provide them with maps of their reserve ‘that [they] may not be robbed of it’: A.J. Ray, J.R. Miller & F. Tough, Bounty and Benevolence: A History of Saskatchewan Treaties (Montreal & Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press) (2000), at 199. However, tribal representatives also frequently spoke their assertions in terms of ancestral and lived local knowledge, of the land as support and sustenance or simply of belonging. A Tlingit chief stated in 1915 that he was unable to point out places on a map that he would like included in the future reserve, but knew how big his land was ‘because it belongs to me. … We give the names to the places around here and those old names come from our old forefathers’.32xCited in Harris, above n. 23, at 233. Chief Gosnell of the Nass River informed the McKenna-McBride commissioners that his people ‘were practically born amongst these trees… we use this [land] for a working ground both to support our children and also our old men’.33xCited in Harris, above n. 23, at 234. But while the adoption of cartographic artefacts was undoubtedly a constraining and alien form of representation for many Indigenous peoples, the production of colonial maps themselves was often heavily reliant on the local geographical expertise of Indigenous guides and so constituted a hybrid of European and Indigenous knowledges.34xD. Bernstein, ‘Negotiating Nation: Native Participation in the Cartographic Construction of the Trans-Mississippi West’, 48 Environment and Planning A 626, at 627 (2016); D. Turnbull, ‘Mapping Encounters and (En)countering Maps: A Critical Examination of Cartographic Resistance’, 11 Knowledge and Society 15, at 40 (1998); Harley, above n. 1; B. Mundy, The Mapping of New Spain: Indigenous Cartography and the Maps of the Relaciones Geográphicas (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) (1996). That expertise was itself traditionally represented in alternative cartographic forms, like the representations of Ojibwa (Anishnabe) migration routes inscribed on birchbark scrolls,35x See Figure 6. European explorers were sometimes surprised by the accuracy and detail of maps produced by their Indigenous informants: see R. Rundstrom, ‘A Cultural Interpretation of Inuit Map Accuracy’, 80 American Geographical Society 155 (1990). or the performative artefacts of songs, stories and rituals.36xM. Warhus, Another America: Native American Maps and the History of Our Land (New York: St. Martin’s Press) (1997), at 3; D. Woodward and G.M. Lewis, Cartography in the Traditional African, American, Arctic, Australian, and Pacific Societies (Chicago : University of Chicago Press) (1998); G. Eades, Maps and Memes: Redrawing Culture, Place, and Identity in Indigenous Communities (Montreal and Kingston: McGill-Queen’s University Press) (2015).

Widespread use of conventional cartography by North American Indigenous peoples in the 20th century was spurred by increasing assertions of land rights, sovereignty and self-determination, and by government regimes for their recognition. This began in a systematic way with the US Indian Claims Commission from 1946,37x See A.J. Ray, ‘Native History on Trial: Confessions of an Expert Witness’, 84 Canadian Historical Review 253, at 256 (2003) and I. Sutton, ‘Cartographic Review of Indian Land Tenure and Territoriality: A Schematic Approach’, 26 American Indian Culture and Research Journal 63, at 76 (2002). and in Canada and Alaska, in the 1970s with the instigation of planning for several mega-projects such as hydro-electricity schemes or oil and gas pipelines. The earliest court cases in Canada to consider inherent rights did not rest on detailed proof of land use or tenure and so did not require complex maps – for example in the Nisga’a litigation begun in 1967, plaintiffs sought a declaration of broad legal principle that their title to land existed at common law without having been extinguished.38xThe Crown’s admission of Nisga’a occupation of the Nass Valley since ‘time immemorial’ also forwent the need for lengthy and detailed land-based evidence. ‘Frank Calder and Thomas Berger: A Conversation’, in H. Foster, H. Raven & J. Webber, Let Right be Done: Aboriginal Title, the Calder Case and the Future of Indigenous Rights (Vancouver: UBC Press) (2007), at 43-47. Earlier cases largely concerned treaty rights and focussed on textual interpretation rather than land use: see R. v. White and Bob, [1965] SCR vi, 52 DLR (2d) 481; Sikyea v. The Queen, [1964] SCR 642, (1964), 43 DLR (2d) 150. The map accompanying the Nisga’a claim in Calder v. B.C.39x Calder v. A-G British Columbia, [1973] SCR 313, 34 DLR (3d) 145. indicated simply the outline of the territory for which the declaration was sought, based on the metes and bounds description of a 1913 Nisga’a petition.40xBrealey, above n. 21, at 71. Likewise, the Federal government’s comprehensive land claims policy, launched in 1973 following the recognition by the Court in the Nisga’a litigation that Aboriginal title formed part of the common law in Canada, required at that stage only basic information about the claimant group, and approximate descriptions of boundaries.41x Ibid., at 73.

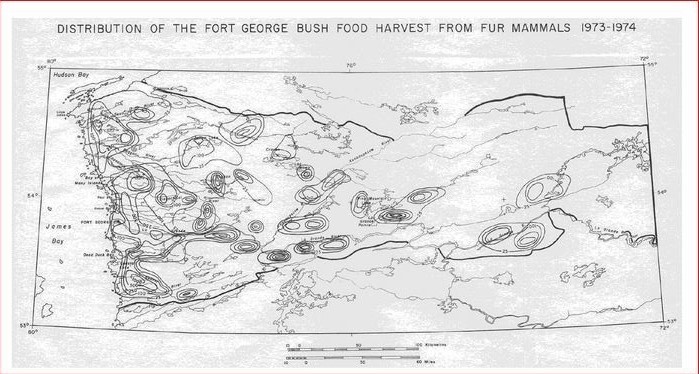

In general, though, the use of litigation as a strategy necessitated the production of maps that would meet the rigorous evidentiary demands of the courts. When the Crees of James Bay (Eeyou Istchee) filed for an injunction in 1972 against the planned hydroelectric project in Northern Quebec, for instance, they had to provide detailed evidence of the specific ways in which the development would impact on their rights.42x Kanatewat v. The James Bay Development Corporation, [1975] 1 S.C.R. 48; (1974), 41 D.L.R. (3d) 1. To show this, Eeyou witnesses were each asked to mark out hunting and trapping territories on a map of the province and to enumerate answers to quantitative questions about species hunted, reliance on traditional foods and access to traplines (family hunting territories).43xH. Carlson, Home Is the Hunter: The James Bay Cree and Their Land (Vancouver: UBC Press) (2007), at 212-20. Such answers required witnesses to think in alien terms about their land – through numbers, statistics and hypotheticals (which some simply refused to do).44x Ibid., at 216-17. Nevertheless, the Cree began negotiating with the Quebec government in 1974 and engaged in an intensive mapping project. Because of the prevailing assumption that they had abandoned their traditional way of life, their maps focussed less on delimiting an area of occupation, and more on documenting hunting and harvesting practices, and quantifying amounts of food produced (Figure 1).45xJ. Bryan and D. Wood, Weaponizing Maps: Indigenous Peoples and Counterinsurgency in the Americas (New York: Guilford Press) (2015), at 66.Figure 1: Distribution map of Cree food harvesting from M. Weinstein, What the Land Provides: An Examination of the Fort George Subsistence Economy and the Possible Consequences on It of the James Bay Hydroelectric Project (Montreal: Grand Council of the Crees) (1976), reproduced in Bryan and Wood, n. 45, at 65.

The legal landscape since then has only expanded the place and importance of maps in the interactions between Indigenous peoples and the state. The consolidation, following Calder, of a jurisprudence of Aboriginal title based on exclusive occupation – to be detailed in the next part – requires documentation of the regular use of, capacity to control or strong presence throughout the territory claimed.46x See Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, [1997] 3 SCR 1010, at 144, 155 and Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia, [2014] 2 SCR 256, 2014 SCC 44, at 33-38. In 1990, the Federal government revised its claims policy so as to place more stringent evidentiary conditions on accepting claims, including ‘a documented statement … that [the group] has traditionally used and occupied the territory in question … a description of the extent and location of such land use and occupancy … together with a map outlining approximate boundaries… the names of bands, tribes or communities … the claimants’ linguistic and cultural affiliation and approximate population figures for the claimant group’.47xPrime Minister Brian Mulroney in a 25 September 1990 speech to the House of Commons, cited in Brealey, above n. 21, at 92. The vast majority of Indigenous groups (around 130) have pursued these negotiated settlements of their claims, rather than litigate them. Finally, the proliferation of environmental, and land and resource management regimes also requires the collection and analysis of large amounts of data relating to Indigenous interests even in areas where Aboriginal title is considered by Canadian law to have been extinguished by treaty. More recent developments in Aboriginal rights jurisprudence have formalised a ‘duty to consult’ wherever proposed governmental actions – such as building a road or issuing a forestry permit – will impact on Aboriginal rights like hunting or fishing.48xD. Newman, The Duty to Consult: New Relationships with Aboriginal Peoples (Saskatoon: Purich Publishing) (2009). Broadly, as David Natcher notes, maps increasingly serve ‘to articulate visually the conflict that exists, or may exist, between Aboriginal land use patterns and resource development initiatives.’49xD. Natcher, ‘Land Use Research and the Duty to Consult: A Misrepresentation of the Aboriginal Landscape’, 18 Land Use Policy 113 (2001).

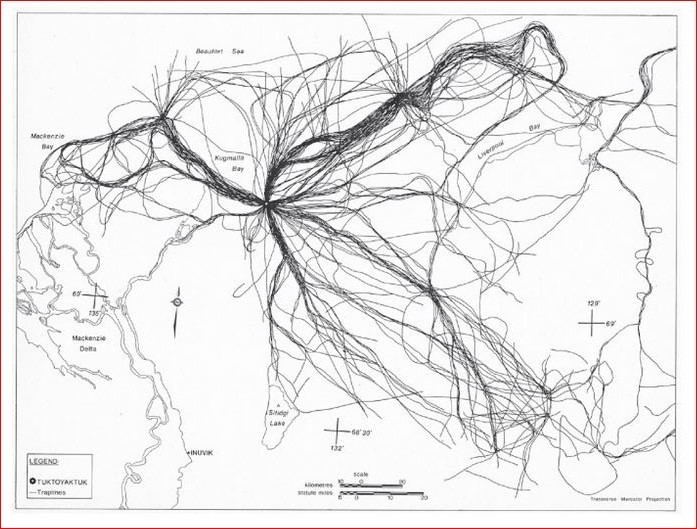

In parallel, conventional cartographic methods have been adapted to both the particularities of Indigenous territorial relations and the exigencies of state processes. In addition to the James Bay Cree study, the first large-scale mapping projects in the 1970s were a comprehensive survey of Inuit land use and occupancy, completed in anticipation of a land claim,50xM. Freeman, ‘Looking Back – and Looking Ahead – 35 Years After the Inuit Land Use and Occupancy Project’, 55 Canadian Geographer 20 (2011). and Dene work depicting their knowledge of the land done for the inquiry into the potential impacts of the Mackenzie Valley Pipeline.51xF. Duerden and R. Kuhn, ‘The Application of Geographic Information Systems by First Nations and Government in Northern Canada’, 33 Cartographica 49 (1996). Peter Usher notes that cartographical innovations in these latter projects were, first, the use of individual ‘biographical mapping’ that charted the subsistence activities of individuals through time and space as paths on the map, collated to produce a visual summary of intensity and geographical extent of use by a community as a whole (Figure 2), and, second, the recording of people’s understanding of the land in terms of ecological knowledge, sites with sacred, ceremonial or narrative significance, quarries, fish traps and place names.52xP. Usher, ‘Environment, Race and Nation Reconsidered: Reflections on Aboriginal Land Claims in Canada’, 47 Canadian Geographer 365 (2003). Note the use of participant observation in these methods that date back to the work of Franz Boas in the early 20th century: Chapin et al., above n. 8, at 621. From the 1980s, emerging geographical information systems (GIS) technologies were becoming more reliable and more readily available.53xDuerden and Kuhn, above n. 51. Land-use and occupancy research, which collects data relating to a particular activity (name of person, time, activity, location), can be indexed to a point or polygon on the map and readily collated and analysed. With portable global positioning systems (GPS), precise locations are readily logged by community members or researchers while out on the land. Digitised land use studies can produce a quantified snap-shot of the territory, useful to state agencies who want to be able to quickly assess the impact of a development project or the amount of compensation to be paid.54xNatcher, above n. 49.Figure 2: Inuit map biography from M. Freeman (ed.), Inuit Land Use and Occupancy Project Report, Vol. 1: Land Use and Occupancy (Ottawa: Department of Indian and Northern Affairs) (1976), at 231, reproduced in Bryan and Wood, n. 45, at 62.

The capacity of these maps to represent Indigenous interests in the powerful, objective language of technology, and to assert jurisdiction and thus counter-map an intervention in the colonial mythology of Indigenous absence, has been celebrated.55xB. Nietschmann, ‘Defending the Miskito Reefs with Maps and GPS: Mapping with Sail, Scuba and Satellite’, 18 Cultural Survival Quarterly 34, at 37 (1995); T. Harris and D. Weiner, ‘Empowerment, Marginalization and “Community-integrated” GIS’, 25 Cartography & Geographic Information Systems 67 (1998). Moreover, there is a sober realism in statements such as the one by Maasai leader Alais Ole-Morindat in the epigraph that it is better to map oneself than to be inevitably mapped by others. I will offer a critique of the specific visual and technological limitations of maps in Part 2. However, it is also important to note that while Indigenous peoples can participate effectively in mapping projects, and can develop alternative cartographies driven and shaped by their own ‘theories of being,’56xA. Ole-Morindat, cited in ‘Community Mapping and Landscape Modelling’ Centre for Indigenous Conservation and Development Alternatives <www.cicada.world/research/themes/community-mapping> (last visited 21 December 2017). laws and political projects, there are multiple and entrenched factors pitched against meaningful participation.57xFor an extended analysis of ‘capacity deficit’ due to social suffering in the context of land claims, see S. Irlbacher-Fox, Finding Dahshaa: Self-Government, Social Suffering, and Aboriginal Policy in Canada (Vancouver: University of British Columbia) (2009). Indigenous communities in Canada are struggling with the trauma of compounded injustices over centuries that have often left them with debilitating levels of poverty, disease, addiction, and violence.58xT. Alfred, ‘Colonialism and State Dependency’, 5 Journal of Aboriginal Health 42 (2009). Historically, in addition to forced relocations and the radical change in ways of life that this often wrought, the Indian Act [‘the Act’] explicitly prohibited cultural and spiritual practices, and undermined existing forms of governance.59xK. Pettipas, Severing the Ties that Bind: Government Repression of Indigenous Religious Ceremonies on the Prairies (Winnipeg: University of Manitoba Press) (1994). It fractured communities by requiring women who married out of their band to leave and denying ‘Indian’ rights under the Act to individuals with fewer than two Indian grandparents.60xP. Palmater, Beyond Blood: Rethinking Indigenous Identity (Vancouver: Purich Publishing) (2011), at 28-42. It vested ultimate ownership of even remaining reserved lands in the Crown.61x See s.18 Indian Act RSC 1985, c.I-5. Residential schools policies forced or persuaded families to send their children to boarding schools where they often suffered physical and sexual abuse, were prohibited from speaking their language, and had difficulties maintaining contact with their relatives or integrating back into their communities.62xTruth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, Summary of the Final Report: Honouring the Truth, Reconciling for the Future (2015) <www.trc.ca> (last visited 21 December 2017).

In the face of this suffering, there are often very few individuals in Indigenous communities who are able to develop the expertise required to become cartographers, and communities inevitably rely on an industry of outside experts. The scene painted by Colin Samson of meetings to prepare maps for the comprehensive claim of the Innu of Labrador – of largely passive Innu ‘participants’ and babbling specialists from the south with their panoply of maps, bullet points, and laser pointers, their quick ripostes to every concern about the inaccuracies of the maps, and constant reminders of the hard facts of what the state will and will not accept – is unfortunately not atypical.63xC. Samson, A Way of Life That Does Not Exist: Canada and the Extinguishment of the Innu (New York: Verso Books) (2003), at 65-72. The experts may now be nominally hired by the Innu, but the scene is reminiscent of earlier ones where maps were clearly instruments of colonial power. Further, and as the following part will explain, the processes themselves in which Indigenous interests may be represented – whether in litigation to establish Aboriginal title under the common law, negotiations to reach a Comprehensive Land Claim Agreement or a myriad of administrative mechanisms – are loaded in favour of the Crown and in many ways continuous with colonial policies of dispossession and assimilation.64x See for example G. Coulthard, Red Skin, White Masks: Rejecting the Colonial Politics of Recognition (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press) (2014). -

2 Sui Generis Aboriginal Title, ‘Other’ Evidence and Different Concepts of Property

We will now turn to the more technical aspects of both Aboriginal title jurisprudence and cartography, since the role that maps currently play in Indigenous claims in Canada is partly shaped by the way that the concept of Aboriginal title has developed, and in particular, by its focus on European proprietary concepts such as exclusive possession that correspond so neatly to the visual geometry of conventional maps. The earliest claims of Aboriginal title put before the courts on behalf of Indigenous plaintiffs in Canada pulled together two centuries of British imperial common law relating to the acquisition of new territory by the Crown, colonial policy and practice such as treaty-making and the ‘Marshall decisions’ on Indian title by the US Supreme Court from the early 1800s.65xFor a comprehensive overview of the development of the doctrine of Aboriginal title across jurisdictions, see P. McHugh, Aboriginal Title: The Modern Jurisprudence of Tribal Land Rights (Oxford: Oxford University Press) (2011), and for this point, at 77, 117. At its simplest, this doctrine was that the right claimed derived from Aboriginal – that is to say, precolonial – occupation of land, and was proprietary in nature.66x Guerin v. The Queen, [1984] 2 SCR 335; McHugh, above n. 65, at 70. The idea that long physical possession could be the root of title was deeply familiar to common lawyers.67xK. McNeil, Common Law Aboriginal Title (Oxford: Clarendon Press) (1989), at 73; B. Slattery, ‘Understanding Aboriginal Rights’, 66 Canadian Bar Review 727 (1987). However, when the Gitxsan and Wet’suet’en brought the Delgamuukw case in 1987 and framed their title as grounded in their own jurisdiction, a second source was accepted by the Supreme Court of Canada: Aboriginal laws and customs providing a connection of the claimants to the territory claimed.68x Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, [1997] 3 SCR 1010, at 126. This articulation of a dual source – common law and Aboriginal law – for title means it is sui generis, or unique, and opens the way for distinctive content for the rights, distinctive means of proof and distinctive forms of representation.69xThe alternative source in the ‘relationship between common law and pre-existing systems of aboriginal law’, Delgamuukw, above n. 68, at 114, also builds on definition of Aboriginal rights more generally in R. v. Van Der Peet, [1996] 2 SCR 507 [Van Der Peet], which sources rights both in prior occupation, and in the prior social organisation and distinctive cultures of Aboriginal peoples on the land, at 74.

Precolonial occupation has become the foundation of contemporary Aboriginal title in Canada, as well as of the alternative political route of negotiating comprehensive claims under Federal policy. However, the perverse function of Indian title historically was to permit, at least from the perspective of colonial authorities, the formal extinguishment of that title by agreement.70x See Banner, above n. 21. This pattern largely continues through the land claims process in Canada today, since government policy is to offer recognition of extensive rights in only a small proportion of the total claim area in exchange for the surrender of rights over – and thus the certainty of state access to – the remainder of the territory.71xC. Samson, ‘Canada’s Strategy of Dispossession: Aboriginal Land and Rights Cessions in Comprehensive Land Claims’, 31 Canadian Journal of Law & Society 87 (2016). Further, the recognition of a proprietary right held by Indigenous peoples by Chief Justice Marshall was accompanied by a declaration that their sovereignty was diminished, that they were ‘domestic dependent nations’ subject to the authority of the United States.72x Johnson v. McIntosh 21 U.S. (8 Wheat.) 543 (1823); Cherokee Nation v. Georgia 30 U.S. (5 Pet.) 1 (1831). This same hierarchy persists in Canadian jurisprudence in the susceptibility of Aboriginal rights to be infringed by government action,73xThe test for infringement was developed in R. v. Sparrow, [1990] 1 S.C.R. 1075. the prospect of which calls for the visualisation of impact, damage and disturbance to Indigenous interests through maps. The recognition of Indigenous rights is at once an affirmation of their ‘infinite violability.’74xI am grateful to one of the anonymous reviewers for this poignant phrase.

The sui generis character of Aboriginal title means that its content is neither a facsimile of fee simple ownership in the common law, nor simply reflective of forms of ownership under Indigenous legal orders, but must be understood by reference to both perspectives.75x Delgamuukw, above n. 68, at 112. For example, one element of colonial policy from the 17th century and Indian title historically was the inability of Indigenous peoples to alienate it to any parties but the Crown. With the purpose of ensuring governmental monopoly over the market in Indian title and protecting Indigenous peoples from unscrupulous settlers, it was justified from a common law perspective because the land title of English subjects was of conceptual necessity derivative from Crown grant.76xThis is one of the modern hold-overs of the feudal system of land tenure in England: McHugh, above n. 65, at 111. However, in Delgamuukw, Chief Justice Lamer speculates that the inalienability of Aboriginal title lands also reflects the degree to which lands are more than a fungible commodity to Indigenous communities who have a special relationship with land that arises over long occupation and use.77x Delgamuukw, above n. 68, at 129. Among the critical commentary on the paternalism of this principle in the present day, see K. McNeil, ‘Self-government and the Inalienability of Aboriginal Title’, 47 McGill Law Journal 473 (2002). In terms of proof, the courts are instructed to be conscious of ‘the special nature of Aboriginal claims, and of the evidentiary difficulties in proving a right which originates in times where there were no written records.’78x Van Der Peet, above n. 69, at 80. Following the elaboration of a sui generis title in Delgamuukw, Chief Justice Lamer then held that Aboriginal laws and customs – such as those regarding tenure, land use or trespass – are relevant as an alternative way to prove prior exclusive occupation.79x Delgamuukw, above n. 68, at 157. Consequently, the evidentiary challenge is conceptual as well as simply pragmatic: oral traditions may be accepted as proof of the truth of factual statements relevant to land holdings contrary to the evidentiary rule against ‘hearsay’;80xSuch statements can usually readily be comprehended within two standard exceptions to hearsay, as declarations by deceased persons relating either to community acknowledgement of public rights (‘reputation’) or as declarations of family genealogy and history (‘pedigree’). but these traditions themselves typically fuse ceremony or performative practices, what judges often refer to as ‘mythology,’ and historical fact. Adopting flexible laws of evidence as part of the reconciliatory bridging of Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal cultures, and the attempt to give equal weight to both perspectives,81x Delgamuukw, above n. 68, at 81. then, often struggles with some foundational epistemological categories.

As many critics have pointed out, this reconciliatory exchange is decidedly lop-sided.82x See for instance, J. Borrows, ‘The Trickster: Integral to a Distinctive Culture’, 8 Constitutional Forum 27 (1997); R. Barsh and J.Y. Henderson, ‘The Supreme Court’s Van Der Peet Trilogy: Naïve Imperialism and Ropes of Sand’, 42 McGill Law Journal 993 (1996-1997); Coulthard, above n. 64. State sovereignty and jurisdiction is assumed; the Crown does not have to base its cadastre or territorial maps on ethnographic interviews mined for travel routes and food weights. Doctrinally, the effort to give weight to Indigenous perspectives is explicitly limited to what is cognisable to the common law. For instance, only customary associations with land that resemble exclusive occupation will give rise to Aboriginal title as that characteristic is taken as a ‘core notion’ of title per se. In the R. v. Bernard litigation, Mi’kmaq elder Keptin Steven Augustine submitted in evidence that the fundamental principle guiding Mi’kmaq tenure was the obligation to share the land, rather than to exclude others. The trial judge suggested that this attitude – although founded in Indigenous legal orders – would be fatal to establishing Aboriginal title.83x R. v. Bernard, [2000] 3 C.N.L.R. 184, [2000] N.B.J. No. 138 (QL). One reason for an unwillingness to compromise on the need to establish exclusive occupation may be that the remedies available to holders of Aboriginal title as a recognisable right in the land are themselves matched to the right to exclude others, and, in Bernard, the courts wanted to foreclose the possibility of recognising Indigenous exclusive possession over large parts of the Maritime provinces. See S. Imai, ‘Sound Science, Careful Policy Analysis, and Ongoing Relationships: Integrating Litigation and Negotiation in Aboriginal Lands and Resources Disputes’, 41 Osgoode Hall Law Journal 587 (2003), at 600.

More contentious, and prevalent, in litigation has been the issue of what kinds of acts, or what degree of usage will constitute ‘occupation.’ The common law has long developed a context-sensitive test for possession: acts indicating intention to possess and demonstrating actual control in an urban neighbourhood, for instance, are more intense than for a sunken shipwreck.84xIn cases such as The Tubantia, [1924] P 78, [1924] All ER 615. In Delgamuukw, CJ Lamer provides an indicative list of activities that will assist in proving exclusive occupation, including: construction of dwellings, cultivation and enclosure of fields and ‘regular use of definite tracts’ for exploiting resources.85x Delgamuukw, above n. 68, at 149. In the Marshall and Bernard Supreme Court decision, his statement was taken to require ‘intensive’ rather than ‘proximate’ use of specific sites,86x R. v. Marshall; R. v. Bernard, [2005] 2 SCR 220, 2005 SCC 43. and in the Tsilhqot’in litigation that followed, there emerged in argument a distinction between a ‘postage stamp’ understanding of occupation in which Aboriginal title would attach only to a patchwork of specific isolated sites, and the ‘territorial claim’ which would encompass a continuous territory incorporating these sites as connected from an Indigenous perspective.87x Tsilhqot’in Nation v. British Columbia, [2014] 2 SCR 256, 2014 SCC 44. See J. Woodward, P. Hutchings & L.A. Baker, ‘Rejection of the “Postage Stamp” Approach to Aboriginal Title: The Tsilhqot’in Nation Decision’, Report Prepared for the Continuing Legal Education Society of British Columbia (2008). The Supreme Court accepted the territorial claim, stating that the common law’s contextual approach includes not only the kind of land but also the way of life of the claimant group and the manner, within their legal systems, that possession might be constituted.88x Tsilhqot’in, above n. 87, at 41. It is not contemplated, however, that possession and exclusion, let alone the kind of land that can be mapped, may not figure in or be comprehensible within the legal system in question.

Thus, while different forms of evidence have – with difficulty – been accepted for the purpose of proving historical occupation, the basic premise that Aboriginal title of necessity involves a discrete group of people ‘filling up’, through their occupation, a bounded, territorial space and is therefore inherently ‘mappable’ is taken for granted. More deeply, there is an assumption that the land being subjected to title is actually constituted by its mappable qualities: that it is coterminous with Euclidean space, and that the qualities of measurable surface area, perimeter and relative position, the logic of numbers, by which land is known and made meaningful as property are simply facts that inhere in the land.89xH. Verran, ‘Re-Imagining Land Ownership in Australia’, 1 Postcolonial Studies 237 (1998); Reilly, above n. 8; K. Anker, ‘The Truth in Painting: Cultural Artefacts as Proof of Native Title’, 9 Law Text Culture 91 (2005). Cartesian spaces can be divided and subdivided by means of boundaries; they are a priori commensurable and interchangeable, properties that facilitate the idea of land as the object of infinite capitalist exchange.90xN. Blomley, ‘Landscapes of Property’, 32(3) Law & Society Review 567, at 575 (1998). As the following examples show, the presumptions operating in Aboriginal title regimes and the broader range of legal and political forums in which Indigenous people are producing maps have created difficulties for representing Indigenous political organisation and relations to place, specifically because of the reductionist and static qualities of conventional maps.2.1 Boundaries

Boundaries are a basic element of any land claim as an expression of the geographic extent of the claim, but drawing them is often a contentious practice, particularly between neighbouring Indigenous groups. This is partly because boundaries on the ground imply boundaries between people, whereas there are likely to be complex kinship and ancestral connections between people who now live in specific locations and identify with specific First Nations, Métis or Inuit communities. It is also partly because, historically, there were areas of overlapping use, and boundaries were left deliberately vague or were simply unimportant unless they were contested.91xAlthough the fact that they were asserted in the face of infringing activities means that boundaries – even strict ones – did exist in some regions in Canada, as Sylvie Vincent argues, based on the history of what would now be called blockades in Quebec during the fur trade era: ‘“Chevauchements” Territoriaux: Ou Comment l’Ignorance du Droit Coutumier Algonquien Permet de Créer de Faux Problèmes’, 46 Recherches Amerindiennes au Québec 91 (2016). The difficulty with mapping boundaries may also be conceptual. While space and place may well be differentiated, the borders between them may be continually shifting and indeterminate or contingent,92xR. Howitt, ‘Frontiers, Borders, Edges: Liminal Challenges to the Hegemony of Exclusion’, 39 Australian Geographical Studies 233-45, at 239 (2001). or the boundary itself may be important as a point of crossing over or connection, rather than of exclusion.93xIn the Australian context, see N. Williams, ‘A Boundary Is to Cross: Observations on Yolngu Boundaries and Permission’, in N. Williams and E. Hunn (eds.), Resource Managers: North American and Australian Hunter Gatherers (Boulder: Westview Press) (1982).

For example, as Paul Nadasdy describes social organisation amongst peoples in the Yukon in northern Canada prior to the intrusion of colonial structures, small hunting groups with flexible membership would travel an annual subsistence ‘round’ over large distances, their composition changing with the availability of resources, social tensions, marriage and trading relations.94xP. Nadasdy, ‘Boundaries among Kin: Sovereignty, the Modern Treaty Process, and the Rise of Ethno-Territorial Nationalism among Yukon First Nations’, 54 Comparative Studies in History and Society 499 (2012). While ethnographers were able to identify distinct language groupings, these were not geographical divisions; nor were they primary for the people themselves, who had their own complex and cross-cutting systems for identifying people that were relative to the ‘vantage points in time and space of both the classifier and the classified.’95xCiting ethnographer Catherine McClellan, Nadasdy, above n. 94, at 508. The concentration of populations around trading posts, and then from the 1940s, the administrative division of people into ‘bands’ under the Indian Act associated with a specific reserve have shaped the contemporary political structure of current-day First Nation groups in the Yukon who have signed off on land claim agreements covering ‘traditional territories’. Left by outside governments to determine claim areas themselves, the fourteen Yukon bands drew up territorial boundaries based on different criteria – some inclusive of all historical use and occupancy of members and their ancestors, others more restrictive – producing a regional land claim map with considerable overlap between territories. Under the agreements, boundaries delimit the jurisdiction of resource management boards and governing councils, and Federal policy has required First Nations to resolve any overlap before certain provisions of the agreement will apply, so as to avoid conflict – to draw ‘boundaries among kin’.96x Ibid., at 512. And as Nadasdy observes, these territorial maps model an ethno-nationalism and form of governance – a previously unthinkable ‘us and them’ – that is now adopted by many people in the Yukon.97x Ibid., at 523.

In his discussion of boundaries within the Hul’qumi’num Treaty Group in British Columbia, Brian Thom highlights that the boundary mapping problem exists because the discontinuous territories that Cartesian borders presuppose are inconsistent with the way that ‘territorial relationships [for Coast Salish peoples] are underwritten by a relational epistemology’ – that is, relationships are themselves a way of knowing the world.98xB. Thom, ‘The Paradox of Boundaries in Coast Salish Territories’, 16 Cultural Geographies 179, at 179 (2009). Instead of numbers and measured qualities, Coast Salish know the land through the mediation of stories about transformer beings who created features of the landscape, and whose spirits continue to be encountered in these places, and through the kinship-based systems of use, sharing and reciprocity that they reinforce. Individuals experience territories not as ‘spaces’ but rather as storied itineraries that people travel for trade, visiting kin, partaking in ceremonies and festivals as well as harvesting.99x Ibid., at 186. Like Nadasdy, Thom observes that bounded territories in land claims tend to elevate tribal bureaucrats and centralised governments ahead of these pervasive kin networks that were once responsible for decisions about resource use and access.100x Ibid., at 182.

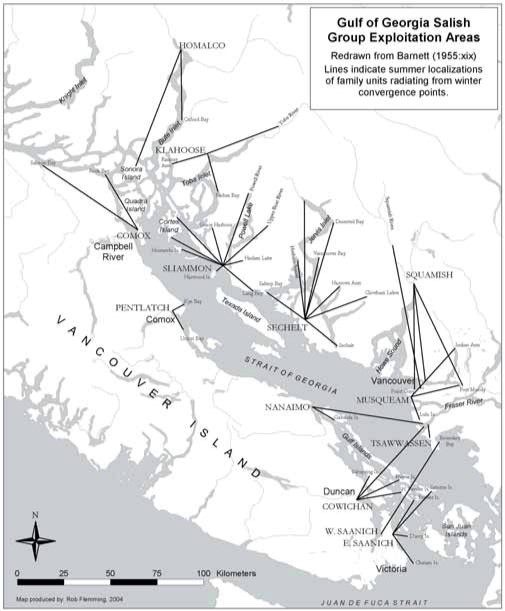

But even within these relational, non-Euclidian networks, the principle of sharing has limits for those who overstay their welcome or fail to observe the appropriate protocols, particularly in times of scarcity.101x Ibid., at 186 Further, there is a dilemma in the colonial context if Indigenous place relations are seen as boundary-less, and, by implication, property-less. To address this, Thom suggests a ‘radical’ cartography that attempts to represent ‘relational epistemology of kin, travel, descent and sharing’102x Ibid., at 197. in place of singular, polygonal representations of territory that tend to exacerbate tensions between groups in negotiations. Plotting movement between winter villages and summer camps might, for example, render a map resembling the radial spokes of an airline map (Figure 3). In its iconography, this strategy resembles the Inuit biographical maps mentioned above. Accumulated lines do give the sense of density around sites most frequently used. Nevertheless, the line is a thin creature at best, and it leaves the ‘false impression that the white spaces between the nodes of activity are empty, culture-less places.’103x Ibid., at 199.Figure 3: Salish Group Exploitation Areas redrawn from Barnett (1955) in Thom, n. 98, at 198.

2.2 Reification and Simplification

The paradox of boundaries is thus one example of land-based phenomena and experiences that are difficult to translate into a cartographic format. The concern can be raised more generally that maps misrepresent Indigenous relations to land because they are reductive and objectifying: conventional cartographic signs have a hard time representing contingency and relationality, movement and multiplicity. For example, a map that approximates hunting use by plotting moose kill sites misses out on recording infinitely more complex and holistic understandings of the life cycle of moose, their broader role in the ecosystem and their cultural significance to hunters.104xT. McIlwraith and R. Cormier, ‘Making Place for Space: Site-specific Land Use and Occupancy Studies in the Context of the Supreme Court of Canada’s Tsilhqot’in Decision’, 188 BC Studies 35, at 41. Nor can it capture future patterns, because hunters follow animals and animal migrations might change.105xSamson, above n. 63, at 77. Although some of the early land use studies had included a rich array of information, including place-commentaries and photos, the mainstream appropriation of TUS as an inventory of land use has been criticised for omitting the breadth of place-based practice and knowledge.106xMcIlwraith and Cormier, above n. 104, at 36; N. Markey, ‘Data “Gathering Dust”: An Analysis of Traditional Use Studies Conducted within Aboriginal Communities in British Columbia’, Masters Thesis, Simon Fraser University (2001), at 9.

Time is a crucial dimension that has been bracketed out of conventional static maps, whether as it pertains to experiential aspects of place and space through things that happen, to associated narratives in which events are temporally linked or even to relatively simple changes that happen over time, such as the fluctuation of land use activities or amounts of food harvested. When Keptin Augustine, the Mi’kmaq witness in the Bernard case, spoke to a class of law students about Mi’kmaki (Mi’maq territory), he accompanied his telling of the Mi’kmaq creation story with an account of his people’s movements from summer camps at the mouths of rivers to winter hunting grounds in the tributary watersheds, and with traces of the movement on a chalk board, in the approximate visual style of a biography approach. He finished with a diagram that looked rather like a tree; and indeed, he emphasised this analogy by likening the movement of people to the flow of sap up and down the trunk and branches of a tree with the seasons. Not only was this map uninterested in boundaries, but it was crucially about a time-based flux.

The kinds of abstractions I have discussed are not specific to maps, but are, as anthropologist Tim Ingold argues, symptomatic of a feature of modern thought that he calls inversion, in which life is reduced to things that are in, but not of, the world.107xT. Ingold, ‘Against Space: Place, Movement, Knowledge’, in P. Kirby, Boundless Worlds: An Anthropological Approach to Movement (Oxford: Berghahn Books) (2009), at 29. Land, the environment, fields and forests, buildings and rooms become, in modern thought, vessels – geographical spaces – for containing life rather than part of the process of living. The focus on ‘occupation’ in property law, then, rather than inhabitation or dwelling, is one symptom of this logic. But while we live in places, not space, places are not the isolated sites or destinations that appear in the visual vocabulary of maps. Experientially, places are known through movements that connect them. For inhabitants of places, things do not exist, but occur over time; we might even say that knowledge and cognition are a matter of pathways.108xD. Turnbull, ‘Maps, Narratives and Trails: Performativity, Hodology and Distributed Knowledges in Complex Adaptive Systems – an Approach to Emergent Mapping’, 45(2) Geographical Research 140 (2007). It is inversion that turns them into discrete and atemporal facts.109xIngold, above n. 107, at 29. As the extraction of people from the world, this feature of modern thought has its phenomenological correlative in disenchantment, that movement in which the modern sciences narrowed our field of perception, reducing nature to a de-sacralised, mechanised world that can be mastered by scientific means.110xM. Berman, The Reenchantment of the World (London: Cornell University Press) (1981).

In sum, conventional cartography uses a symbolic economy that historically erased Indigenous presence on the land (ironically in many cases using Indigenous trails, guides or informants to help them do so). Maps traffic in an aesthetic of empty spaces waiting to be filled by European discoveries or the implementation of their legal orders, and thus collude with the legal doctrine of a fictional terra nullius. That visual metaphor remains powerful and unacknowledged. While the Supreme Court decision in Delgamuukw rejected much of the trial judge’s prejudicial assessment of the plaintiffs’ evidence of their laws and tenure systems as unjustly devaluing what is unique about Aboriginal rights,111x Delgamuukw, above n. 68, at 93-106. his repeated invocation of the territory claimed as a ‘vast emptiness’ slips beneath our cognitive radar.112x See discussion in M. McCrossan, ‘Contaminating and Collapsing Indigenous Space: Judicial Narratives of Canadian Territoriality’, 5 Setter Colonial Studies 20, at 25 (2014). This view – literally produced for the judge via aerial views in a helicopter as if to match the bird’s eye view-from-nowhere of the map – can be contrasted with Gitxsan representation of their land as a bountiful, full box.113xR. Daly, Our Box Was Full: An Ethnography for the Delgamuukw Plaintiffs (Vancouver: UBC Press) (2005).

As powerful a tool as counter-mapping has been to reverse the presumption of emptiness, the kind of presence that can be expressed in conventional maps is itself limited, within cartographic vernacular, to dots, lines and polygons, qualified by colour, text, number or other symbol. Map aesthetics are also consonant with the archetype of modern capitalist property. Land is a surface area divided by boundary lines that are necessary to the concept of exclusion, and to distinguishing ‘mine’ from ‘yours.’114xNote that although conventional accounts of the exclusive aspect of liberal property rights rely on this geographical trope, an alternative account of ‘exclusivity’ relates to the primacy of the owner as the person who is able to set an agenda for the thing: L. Katz, ‘Exclusion and Exclusivity in Property Law’, 58 University of Toronto Law Journal 275 (2008). The bird’s eye view constitutes a divide between the observer and the external world in a fantasy of domination that constitutes the conditions for ownership, or erases the very act of seeing by making these qualities of the land seem objectively there, while the homogeneity of the surfaces facilitates the idea of endless exchange.

Thus, even when mapping techniques attempt to express lived places – such as through recording use sites – rather than spaces, they are rendered as isolated points, mere locations in a void. The biographical trail maps perhaps come the closest to visualising time-based movement through territory, but they, too fight against the perceived thinness of the line. Is it that, as Margaret Wickens Pearce asks rhetorically, ‘Western mapping practices are antithetical to expressions of place in some fundamental way such that place can only be expressed by turning away to other expressive forms …?’115xM.W. Pearce, ‘Framing the Days: Place and Narrative in Cartography’, 35 Geography and Geographic Information Science 17 (2008). The following section will canvas some alternative cartographies deployed by Indigenous peoples that, in different ways, alter, challenge or subvert the visual conventions of cadastral-type maps through new technologies, alternative aesthetic forms and even non-representational practices. -

3 Alternative Cartographies

The distortions and simplifications that conventional maps make to produce a flat, usable map from a round, three-dimensional and complex Earth are necessary but not innocent; they have also become largely invisible to us. Within critical cartography, the basic dimensions of standard maps – scale, projection and symbolism – have been rethought in ways that confound these assumptions about what the world ‘looks’ like. For instance, the world map with which most of us are familiar is based on the Mercator projection with north upmost. Designed to facilitate maritime navigation in 1569, it keeps meridian lines parallel in flattening the globe, but enlarges the areas of landmasses towards the north and south poles, thus portraying Europe and North America as more prominent geographically.116xM. Monmonier, Rhumb Lines and Map Wars: A Social History of the Mercator Projection (Chicago: University of Chicago Press) (2004), at 1-3. Its most famous alternative, the Peters projection, abandons the rectilinear projection but keeps the relative area of landmasses, thus reducing the prominence of Europe and North America.117x<www.oxfordcartographers.com/our-maps/peters-projection-map/> (last visited 15 January 2018). But see Mark Monmonier on the simplistic claims of Peters that his map was an antidote to the Eurocentric Mercator: Monmonier, above n. 116, at 145-7.

With the advent of a global Indigenous counter-mapping movement, other kinds of critiques and alternative techniques have emerged. For instance, Inuit mapping projects, in which sea-ice areas are crucial, question the conventional division between land and water, and its focus on mapping in detail only the former. They necessarily represent a surface – ice – which is impermanent and only seasonally present.118x See the Inuit Sea-Ice Use and Occupancy Project: <www.uaf.edu/anthro/iassa/ipyisip.htm. (last visited 29 September 2017); I. Krupnik, C. Aporta, S. Gearheard, G.J. Laidler, L. Kielsen Holm (eds.), SIKU: Knowing Our Ice. Documenting Inuit Sea Ice Knowledge and Use (London: Springer) (2010). Some of the innovation in ‘coding’ information into maps can be attributed to the development of community-based or participatory mapping, where decisions on design are being made by the communities to whom the maps pertain, rather than solely by professional cartographers.119xA ‘second wave’ of Indigenous mapping in which Bernard Nietschmann’s work with the Toleda Maya was a catalyst: Toledo Maya Cultural Council and Toledo Acaldes Association, Maya Atlas: The Struggle to Preserve Maya Land in Southern Belize (California: North Atlantic Books) (1997), at 140. The development of critical cartographic competencies – technical know-how with respect to the tools of cartography married with an understanding of their contingency and significance – in Indigenous communities has been an essential component of Indigenous struggles through counter-mapping.120xJ. Johnson, R.P. Louis & A.H. Pramono, ‘Facing the Future: Encouraging Critical Cartographic Literacies in Indigenous Communities’, 4 ACME: An International E-Journal for Critical Geographies 80 (2006). The variety of alternative cartographies range from sophisticated use of innovative technologies, to drawing on traditional aesthetics and practices in developing alternative visualisations of land, to what might be called non-representational maps.3.1 Alternative Technologies: Digital Mapping and GIS

The use of digital mapping technologies, or cybercartography, has revolutionised cartography in three ways. First, it is possible to store vast amounts of information associated with points on a map, through hyperlinked or layered data, by using interactive interfaces with moveable scales that allow different-sized phenomena to appear when the surface of the map is zoomed in or out, and through 3D and virtual reality projections. These can include multimedia such as photos, videos and audio recordings (and potentially, with advances in virtual reality, smell and touch, too).121xM.W. Pearce and R.P. Louis, ‘Mapping Indigenous Depth of Place’, 32 American Indian Culture and Research Journal 107, at 123 (2008). Second, map production and use have been somewhat democratised: with relatively affordable GPS units that can pinpoint the coordinates of a physical location on the ground; ubiquitous digital maps such as Google Earth or Microsoft Virtual Earth allow users to select and determine map formats, as well as, in Web 2.0, to geo-tag places with their own data. Third, continuous data inputs and remote sensors permit digital maps to show real-time changes such as temperature or ice-thickness.122x See for instance, <www.fourmilab.ch/cgi-bin/uncgi/Earth/action?opt=-p> (last visited 29 September 2017).

The sheer quantity of data that can be digitally associated with location points means that maps are able to represent a more complex sense of place to their audience. Conventional Traditional Use mapping recorded three basic data points: who (participant name), what (type of activity) and where (spatial feature). A larger data packet can, for instance, contain information about repeat use that may have been omitted from use studies to make a cleaner map, but that can now indicate the importance of certain sites, as well as a more nuanced assessment of the likely impact of potential disturbances; time-related data within the packet can help make this same projection into the future.123xR. Olson, J. Hackett & S. DeRoy, ‘Mapping the Digital Terrain: Towards Indigenous Geographic Information and Spatial Data Quality Indicators for Indigenous Knowledge and Traditional Land-Use Data Collection’, 53 The Cartographic Journal 348, at 351 (2016). More complex information, such as how sites are connected to each other, which families or clans participate in particular activities, how the knowledge or practice has been learnt and ecological assessments of the quality and quantity of resources available, can also be captured.124x Ibid. Multiple layers of data can thus be easily accessed from the same map.

But digital technologies could lend themselves to a more powerful shift in cartographic thinking than merely ‘capturing’ more and more complex information about places. Critically, multimedia – drawings, photos of sites or 3D renderings, audio recordings or videos of people telling myths, stories or personal anecdotes and experiences, or texts – can help bring non-quantifiable human emotional and experiential aspects of place into the map. The human, time-based and experiential elements can end up working against the positivist assumption of a real, ascertainable world being represented. Crucially, recordings and texts (when read) are themselves time-based experiences for the reader, watcher and listener.

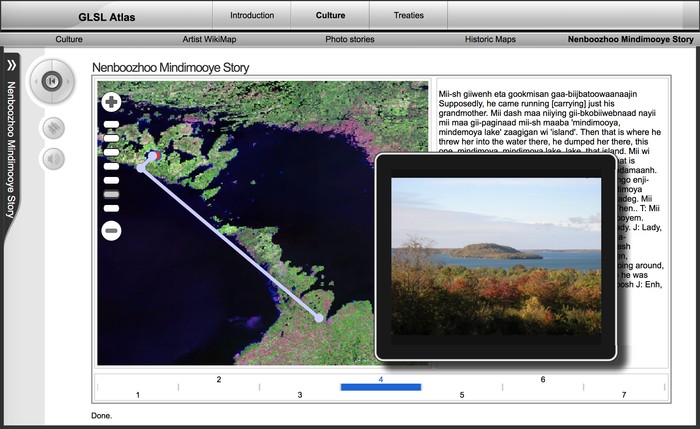

One particularly striking example of an Indigenous mapping project that adopts a ‘performative’ or processual approach is the Cybercartographic Atlas of Indigenous Perspectives and Knowledge of the Great Lakes Region.125xThe Great Lakes region straddles the US and Canada, encompasses Lakes Superior, Michigan, Huron, Erie and Ontario, and is the homelands of the Iroquois, Algonquin and other Indigenous peoples. See S. Cacquard, S. Pyne, H. Igloliorte, K. Mierins, A. Hayes & D.R. Fraser Taylor, ‘A “Living Atlas” for Geospatial Story-telling: The Cybercartographic Atlas of Indigenous Perspectives and Knowledge of the Great Lakes Region’, 44 Cartographica 83 (2009). Using software called Nunaliit,126x See <http://nunaliit.org> (last visited 28 September 2017). the Atlas’ processes are ‘living’ in that the open database allows partner communities to continue to contribute geographical knowledge on an ongoing basis, including via remotely sensed live data, while its readers can access interactive, multimedia modules relating to specific places. In general, the modular structure makes it easier for small uncoordinated groups to contribute content. For example, one module in the ‘Culture’ section of the Atlas tracks a story of Nenboozhoo (the Anishnabe trickster), and the creation of Mindemoya Island, with an interactive map of the journey undertaken in the story. At each stop on the map, one can listen to a section of the story recorded in Anishnabemowin, read the transcript in Anishnabemowin and English and see a photograph of the location (Figure 4).127x See <http://atlas.gcrc.carleton.ca/glsl/culture/nenabush_story/nenabush_story.xml.html> (last visited 28 September 2017).Figure 4: Screenshot: Living Cybercartographic Atlas of Indigenous Perspectives and Knowledge <http://atlas.gcrc.carleton.ca/glsl/culture/nenabush_story/nenabush_story.xml.html> (accessed 15 January 2018).

A similar blend of oral histories or traditions and geographical locations is informing mapping projects on Vancouver Island, this time supported by the Google Earth platform. Through their Outreach program, Google Earth has offered cultural mapping training to over 400 Indigenous individuals since 2007.128xJ. Hunter, ‘Oral History Goes Digital as Google Helps Map Ancestral Lands’, Globe and Mail (July 11, 2014). See also, C. Summerhayes, Google Earth: Outreach and Activism (2015). Anthropologist Brian Thom works with Hul’qumi’num elders, travelling around to key sites, recording stories and plotting them with a GPS on a customised Google Earth map.129x See project description here: <www.uvic.ca/socialsciences/anthropology/people/faculty/thom.php> (last visited 28 September 2017). Indigenous youth from the Hul’qumi’num communities have also been provided with video cameras to speak with elders with the potential to geo-tag aspects of their interviews on the online map.130xHunter, above n. 128. In a parallel project in the Kamchatka region in Russia, Thom and his mapping team have used the satellite 3D imagery view in Google Earth to ‘virtually fly through the landscape’ with their interviewees so as to prompt recollections of those places.131xB. Thom, B. Colombi & T. Degai, ‘Bringing Indigenous Kamchatka to Google Earth: Collaborative Digital Mapping with the Itelmen Peoples’, 15 Sibirica 1, at 17 (2016). One final innovation used by Thom is a combination of an app that records 360° images of sites, together with a cheap attachment for smartphones (some made of cardboard, literally called the Cardboard Virtual Reality Viewer) that renders the images in 3D by introducing a parallax between each eye, thus approaching a surround virtual reality experience for visiting sites.132xB. Thom, personal communication, 12 October 2015.

As these more complex maps are becoming increasingly deployed in interactions with outside governments, the courts or resource industry proponents, their utility lies in their capacity to show, with great visual impact and almost instantaneously, the presence of Indigenous peoples on the land and the rich layers of their knowledge, history and use that the different data recorded represent. To do this effectively, Indigenous counter-mapping has to tread a fine line between being able to represent their differently-configured interests and being legible to those on the other side of the table. As Dallas Hunt and Shaun Stevenson warn, the very strategies used to resist dominant mapping techniques may also circumscribe the kinds of interventions that are possible, and in some cases even re-inscribe elements of settler colonial cartography.133xD. Hunt and S. Stevenson, ‘Decolonizing Geographies of Power: Indigenous Digital Counter-Mapping Practices on Turtle Island’, 7 Settler Colonial Studies 372 (2017). For all its complex informational layers, when the map on the computer is the focus of communication, negotiation and decision-making, it displaces and diminishes the very experiential knowledge that it claims to represent. As Samson puts it, maps doubly dispossess Indigenous peoples by facilitating extinguishment of their Aboriginal title and by supplanting ‘secrets, visions, experience, stories and memories by two-dimensional abstractions.’134xSamson, above n. 63, at 86. Counter-mapping is thus a specific instance of the larger paradox in the politics of recognition in which the extent to which claims based on the distinctness of one party – here, different forms of property – are successful depend on their being rendered in terms of what is familiar to the other.135x See K. Anker, Declarations of Interdependence: A Legal Pluralist Approach to Indigenous Rights (Surrey: Ashgate Publishing) (2014), at 27-62. At the same time, as Alais Ole-Morindat spells out, not participating in the mapping process is untenable.

Two caveats to the problem of recognition might also be added. One is that despite the power imbalance involved in the recognition process, either writ large or in the specific case of cartography, it should not be assumed that the terms of recognition are themselves static. Indigenous interventions in these discourses of power can and do initiate critical shifts in the way terms like property are understood. The second caveat is that we ought not to assume that representations like maps, or verbal descriptions in proprietary terms, can do all the work. Indeed, one of the risks is that when governments and resource industry proponents see the issue as one of having sufficient information about land use in order to calculate impacts, they tend to want to use maps to supplant the direct involvement of Indigenous participants. Specific elements of local knowledge then get taken both out of local context and out of local control.136xNatcher, above n. 49, at 118. Indeed, some argue that the benefits of the practice of ‘participatory mapping’ is that it shifts attention from the map as an object per se, and, as Björn Sletto writes, to the process of mapping as a ‘space of engagement where social and spatial relations are reconfigured, and where representations of these relations will take a multitude of forms.’137xB. Sletto, ‘Indigenous Rights, Insurgent Cartographies, and the Promise of Participatory Mapping’, LLILAS Portal 12, at 14 (2012). In Indigenous research methodologies, place itself may be considered a participant in the mapping process.138xJ. Johnston and S. Larsen, ‘Introduction: A Deeper Sense of Place’, in J. Johnston and S. Larsen (eds.), A Deeper Sense of Place: Stories and Journeys of Collaboration in Indigenous Research (Corvallis: Oregon State University) (2013), at 10. Some communities, recognising the risk of losing control or having their privacy invaded, have consciously kept their maps for themselves, and produced them for their own purposes.139x See comments from Dene mapper Phoebe Nahanni cited in Bryan and Wood, above n. 45, at 69.3.2 Alternative Aesthetics

If GIS introduce technological possibilities for adding to the dimensions in which maps operate and improving their capacities to represent more complex relationships with place, low-tech options also provide alternatives, some of which have been mentioned above: removing ‘familiar’ land marks such as national or provincial borders, roads and modern towns, highlighting alternative places for their cultural significance, plotting use trajectories rather than boundaries, and renaming sites with their Indigenous toponyms (see for example Figure 5). While the cartographic techniques remain the same – and all these innovations use the standard base map that is readily readable by state officials and others – the exchange of the expected with the unfamiliar is destabilising. For instance, reinscribing Indigenous toponyms is not simply the replacement of one name with another, but the utilisation of different naming conventions, and in particular, ones which often reference a relationship with the land from the perspective of the person moving around in it. Gwilym Eades describes James Bay Cree toponyms as often containing information about the place itself, drawn from activities performed at the site, history, mythology or geological features.140xEades, above n. 36, at 54-58. Thomas Thornton observes that amongst the Tlingit, ‘[s]o evocative are Indigenous place names, a speaker who has never even been to a particular site may be able to sense – visually, morally and in other ways – its features and significance.’141xT. Thornton, Haa Léelk’w Hás Aaní Saax’ú: Our Grandparents’ Names on the Land (Juneau: Sealaska Heritage Institute) (2012), at xii-xiii. See also K. Basso, Wisdom Sits in Places: Landscape and Language Among the Western Apache (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press) (1996), at 103.

Figure 5: Nayanno-nibiimaang Gichigamiin (The Great Lakes) in Anishinaabemowin (Ojibwe), with north to the left, by Charles Lippert and Jordan Engel https://decolonialatlas.wordpress.com/2015/04/14/the-great-lakes-in-ojibwe-v2/ (accessed 11 January 2018).

This ‘person-in-place’ perspective can also influence some of the other parameters of cartographic representation, such as scale and projection. A cultural orientation towards the rising sun – such as in the ‘Eastern Door’ of the metaphoric Haudenosaunee longhouse, guarded by the Kanien’kéha (Mohawk) Nation, or in the four directions of the ‘medicine wheel’ common to plains peoples in which East is the direction of beginnings142xL. Pitawanakwat, ‘Ojibwe/Powawatomi (Anishinabe) Teaching’ <www.fourdirectionsteachings.com/transcripts/ojibwe.pdf> (last visited 20 September 2017). – might lead to placing East to the ‘top’ of the map from the perspective of the reader.143xObservation attributed to Jordan Engels, cartographer and founder of the project Decolonial Atlas: Alysa Landry, ‘Lies Your Maps Tell You: Reclaim Native Lands’, Indian Country Today (29 May 2015). An alternative orientation organises the map in terms of the direction of travel, as for the traditional Algonquin birchbark maps mentioned earlier, which depicted migration routes by arranging elements of the route – rivers, lakes and portages – along a linear axis of forward movement rather than according to cardinal directions (Figure 6). In this case, the utility of the map to the person-in-place drives the importance of sequential and linear positioning of major features of the routes. Similar pragmatic concerns give rise to other formats such as the Inuit maps representing bays and inlets along the coast of Greenland, which are carved from small lumps of driftwood, and so are both portable and buoyant, and can be read in the dark.144x‘Inuit Cartography’ Decolonial Atlas <https://decolonialatlas.wordpress.com/2016/04/12/inuit-cartography/> (last visited 20 September 2017).

Figure 6: Red Sky’s Ojibwa Migration Chart, original on 2.6 m birchbark scroll held by Glenbow museum, Alberta, drawing by B. Nemeth in Dewdney, Sacred Scrolls (1975).

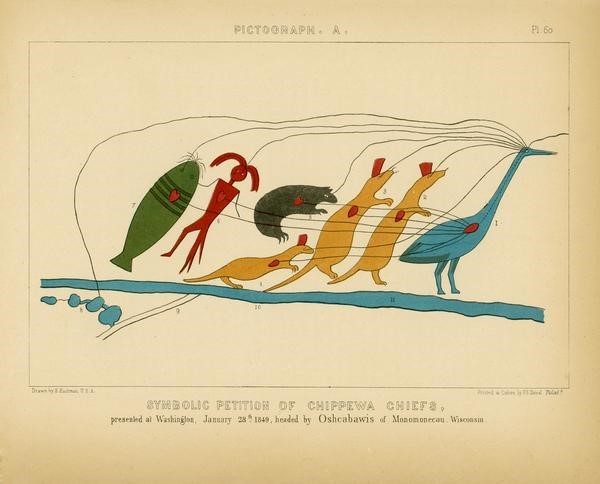

The distinctive aesthetics of embodied relationships to place emerge more forcefully when maps shade into art. In Mischif (Métis) artist Christi Belcourt’s series ‘Land and Water’, she plays with some of the above conventions.145x See: <http://christibelcourt.com/water/> (last visited 20 September 2017). In Goodland, she reproduces two versions of a colonial era map, in which the original labels of one (‘Lake Ontario’, ‘Part of Canada’) are swapped for ‘Onitariio’ and ‘Stolen Land’. A sardonic ‘legend’ contrasts symbolic significance in the two maps, for instance, where tree icons equate to a dollar sign for the first map and ‘lungs of the earth’ for the second. But there are also more subtle ways in which the series of paintings explores that which ‘cannot be found on today’s maps’.146x‘Mapping Roots: Perspectives on Land and Water in Ontario’ <http://christibelcourt.com/Gallery/gallerySERIESmrPage1.html> (last visited 20 September 2017). An elongated canvas, Looking West resembles the linear arrangement of bodies of water in Anishnabe migration charts. Each lake (in white) is ringed with blue, then black, dark red and beige, a contour style echoing the Ojibway Woodland school of painting that makes the lakes appear to thrum with energy. Other visual techniques – swirling lines of bright dots in what appear to be the sky and its reflections in the water in View or in the lake around Manitoulin, or the electrified nerve-like traces in Returning the Copper – similarly render the crackling vibrancy of these places, or produce a sense of being immersed in them. Not only do these paintings constitute maps or representations of land and water as they are experienced by living people in place, but those places are seemingly alive. A more literal connection between people and place can be seen in the ‘Symbolic Petition’ carried by Ojibwa leader Oshcabawis in 1849 to Washington in which the dodem (totemic) figures of the Crane, Catfish, Bear and Marten are connected by lines – from their hearts and eyes to the heart and eye of the Crane as their representative, and from its eye to the lakes that were the subject of the petition (Figure 7).147xR. Satz, Chippewa Treaty Rights: The Reserved Rights of Wisconsin’s Chippewa Indians in Historical Perspective (Madison: Wisconsin Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters, 1991) (1991), at 51.

Figure 7: Chippewa Symbolic Petition, copy in H. R. Schoolcraft, Historical and Statistical Information Respecting the History, Condition and Prospects of the Indian Tribes of the United States (Part 1) (1851), plate 60.

3.3 Alternative Laws?

To date (and to my knowledge), none of these alternative map forms have been used in legal proceedings or in negotiations in Canada as a map. Would it make any difference if they were? In Australia, one high-profile painted canvas – the Ngurrara Canvas II that depicts key sites on the land in their spiritual as well as physical relation to one another – was presented as a map during preliminary hearings before the Native Title Tribunal. In keeping with a distinctive Australian Desert style of painting, the complex ‘organic’ geometry of lines and circles both suggests and destabilises the feeling of an aerial view, while the saturated colours on an oversize canvas (10 by 8 metres) engulf the viewer in the landscape.148x See: <www.nma.gov.au/exhibitions/ngurrara_the_great_sandy_desert_canvas_/home> (last visited 4 January 2018). Although, ultimately, the claimants were still required to submit a conventional map of their claim area, framing the painting as a ‘map of country’, as I have argued elsewhere, puts into relief the fact that all land titles are a ‘complex of habits of vision, practices with respect to the world and the methods of representation that link the two.’149xAnker, above n. 135, at 157. Viewers can let themselves be affected by the contrast between the fullness of the paintings or their visible connections between people and place, and the vacant asceticism of the standard map. The aesthetics of the Ngurrara Canvas speaks to a different type of relationship with the land, a different way of knowing it and thus a different form of property ‘entitlement’.

And yet, non-conventional maps have featured as proof in land claims in Canada if we take maps more broadly as representations of peoples’ relation with place. As Mark Warhus writes of traditional Native American map making generally, visual maps were always a transitory illustration, and ‘secondary to the oral “picture” or experience’ of a multi-dimensional landscape.150xWarhus, above n. 36, at 3. While visual maps are one performance or expression of place, so are dances, songs, stories, crests and even dreams.151xH. Brody, Maps and Dreams: Indians and the British Columbia Frontier (Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre) (1981). For example, the records of the succession of house territories contained in the Gitxsan adaawk recited in connection with crests and songs, and presented as evidence of Aboriginal title in Delgamuukw, also serve as mental maps of the territory of each house.152xDaly, above n. 113, at 251. In that case, the trial judge famously protested that ‘It’s not going to do any good to sing to me. I have a tin ear.’153xJ.E. Chamberlain, ‘Close Encounters of the First Kind’, in J. Lutz (ed.), Myth and Memory: Stories of Indigenous-European Contact (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press) (2007), at 25. In the wake of the Van Der Peet case discussed above, judges are now directed to take on board Aboriginal perspectives on evidence, which potentially includes songs and art as alternative cartographies. But perhaps it is inevitable that most of us who are not trained to hear and read such maps have tin ears (and eyes). We have many things to learn and unlearn before this will change.

Of the many things that the mainstream Canadian legal system still has not confronted in its encounter with and ‘recognition’ of Indigenous legal traditions is the assumption that anything that matters can be written down, in propositional words and phrases, or on a scientific map. First, this does not notice that behind or within the oral traditions that form part of the evidence are protocols, laws about who can speak about or show what, when, to whom and in what way.154xV. Napoleon, ‘Delgamuukw: A Legal Straightjacket for Oral Histories?’, 20 Canadian Journal of Law & Society 123, at 126 (2005). Second, it denies the performative element both of law, and of cartography. All knowledge is made by being and moving somewhere with our bodies.155xTurnbull, above n. 108, at 142. While in this text I have concentrated on arguing this in the context of cartography, the same is true of law.156x See B. Hibbits, ‘Making Motions: The Embodiment of Law in Gestures’, 6 Journal of Contemporary Legal Issues 51 (1995). But the model of legal recognition at play in Aboriginal title is at best one where Indigenous law can be ascertained empirically and produced descriptively.157xK. Anker, ‘Law, Culture and Fact in Indigenous Claims: Legal Pluralism as a Problem of Recognition’, in René Provost (ed.), Centaur Jurisprudence (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press) (2016). Just like maps, forms of Indigenous law like the adaawk are treated as artefacts that can be tested for their veracity and accuracy as depictions of past practices (or rejected as mythology), rather than themselves practices embedded within legal institutions.158xNapoleon, above n. 154, at 154. -

4 Conclusion